[ Dr Sailajananda Saikia ]

Despite comprising eight states (Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, and Tripura), Northeast India only has 3.8% of India’s population. More than 80% of the people in this primarily rural area live in communities and rely on small-scale forestry, agriculture, and other sources of income.

Even with an abundance of natural resources, such as water, minerals, and forests, rural development is nevertheless uneven and characterized by large socioeconomic gaps. These disparities appear within individual states (intra-state), between rural Northeast India and the rest of the nation, and between states within the area (interstate). These disparities have been sustained by historical isolation, geographic difficulties (such as mountainous terrain, floods, and border closeness), inadequate infrastructure, ethnic strife, and unequal policy implementation.

Rural communities in the Northeast have per capita incomes that are 30-50% lower than the national average, despite the fact that the nation’s economy has grown by an average of 6-7% per year.

Northeast states have experienced faster reductions in multidimensional poverty than the national average, with 135 million Indians escaping such poverty between 2015-16 and 2019-21, according to recent data from NITI Aayog’s National Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) Progress Review 2023 (based on NFHS-5, 2019-21).

Rural disparities still exist, though, as evidenced by the region’s MPI headcount ratio falling from 29.17% in 2013-14 to 11.28% in 2022-23 nationwide. Within, regional differences are still quite noticeable, since Meghalaya has one of the highest rural MPI intensities, at 45-50%, because of poor sanitation and nutrition.

India’s total rural literacy rate is 77%, according to the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2023-24. However, rural areas in the Northeast average 75-85%, and gender disparities are growing in states like Nagaland.

Key dimensions of disparities

- Economic disparities

- a) Income and poverty levels: According to the updated NITI Aayog MPI data from 2023, rural poverty headcount ratios in Northeastern states range from 5 to 15%, which is less than the predictions of 10 to 22% during 2011-12. This indicates that programs like PM Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana have made progress.

Mizoram and Sikkim are below 5%, while Tripura and Nagaland continue to record the highest at 12-15% (2022-2023). There are still disparities within the state; in Assam, the average monthly income from tea in the rural Brahmaputra valley is Rs 10,000-12,000, while in highland districts such as Karbi Anglong, it is Rs 6,000-8,000 (NSSO 2023-24 estimates). Rural poverty decreased to 4.86% nationwide in FY24 (SBI Report 2024), however the Northeast lags behind because of yearly flood-related losses that impact 40% of arable land.

- b) Agricultural dependence and underutilization: Subsistence farming still accounts for more than 70% of rural employment, and because of jhum cultivation and inadequate irrigation (only 20-25% coverage compared to 50% nationally, per the 2023 agricultural census), productivity is 20-30% lower than national norms. According to data from 2023-24, states such as Nagaland and Arunachal have yields of 1.5-2 tons/ha of rice, a crucial crop, which is 15-20% lower than Assam’s 2.5 tons/ha.

Jobs in agro-processing and rural electrification are restricted by untapped hydropower, which accounts for 60% of India’s potential. According to a 2024 study on regional agricultural expansion, the Gini coefficients for rural farm incomes in hill states increased to 0.32-0.35, indicating conditional convergence in non-food grains but divergence in food grains.

- c) Inequality trends: Due to unequal non-farm access, rural Gini coefficients have slightly increased to 0.28-0.33 (from 0.25 in 2011-12). Only one-third of agricultural household income comes from farming (NABARD 2021-22, with updates from 2024 demonstrating persistence). This exacerbates disparities whereby urban migration-related remittances benefit valley regions but not isolated hills.

- Infrastructure and access gaps

- a) Connectivity: According to PMGSY 2024 progress reports, the density of rural roads is still 40-50% lower than the national average, and 30% of routes are affected by floods each year in Assam and Manipur. Digital markets are constrained by the rural Northeast’s 25-30% internet penetration rate (compared to 40% nationwide, TRAI 2024). However, more than 5,000 villages have been connected thanks to NESIDS expenditures (Rs 20,000 crore, 2023-24).

- b) Basic amenities: According to Saubhagya 2024, rural areas now have 85-95% better access to electricity, although Meghalaya falls behind at 70% because of its topography. (Swachh Bharat 2023) sanitation coverage is 75-85%, with 65% in Nagaland. In the Manipur highlands, 20-30% of rural households suffer from water shortage (MPI 2023).

- Social and human development disparities

- a) Education and health: Although rural literacy rates have increased from 70% in 2011 to an average of 75-85% (PLFS 2023-24), quality lags-Manipur rural dropout rates are 15-20% (U-DISE 2023). Nagaland is behind at 72%, while Mizoram is ahead at 92%. According to health statistics, life expectancy is between 68 and 72 years (SRS 2023), and maternal mortality in Tripura is 10-20% higher than the rural national average (100/100,000 vs. 85 countrywide).

Meghalaya has the greatest rate of multidimensional health and nutrition deprivation, affecting 15-25% of rural households (NITI MPI 2023).

- b) Gender and ethnic inequalities: Women in rural areas perform 60-70% of agricultural work but own less than 20% of the land, and their literacy rates are 70-80% compared to 80-90% for men (PLFS 2023-24). Gaps are widened by ethnic divisions; in Manipur, hill tribes endure 15% higher MPI than valleys.

- c) Migration and urban-rural divide: Although the gap between rural and urban MPCE has decreased to 70% (HCES 2023-24), youth out-migration has resulted in “ghost villages,” where remittances benefit 20-30% of households while placing a burden on local economies.

Interstate variations

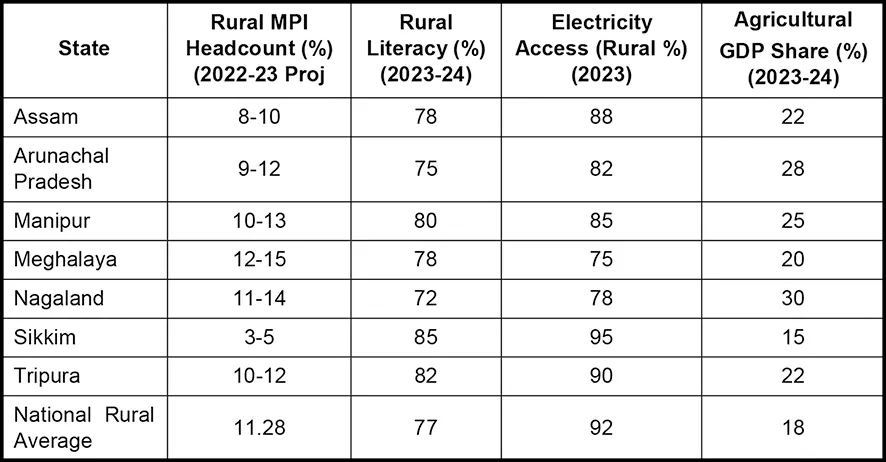

The updated table incorporates NITI MPI 2023 (headcount % for rural-dominant Northeast), PLFS 2023-24 literacy, SRS 2023 electricity (rural %), and Agricultural Census 2023-24 GDP share estimates:

Mizoram and Sikkim lead with low MPI and high literacy, driven by governance and tourism; Nagaland and Meghalaya lag due to conflict and terrain. HDI variations persist, with Northeast states’ rural-adjusted HDI at 0.60-0.70 (medium), vs. national 0.685 (HDR 2025).

- Causes of these disparities:

- a) Geographical and historical factors: Colonial concentrate on Assam neglected highlands; access is restricted by floods and hilly terrain (60 percent area).

- b) Policy and governance: NEC aids provide 90:10 of the central money; however, 15-20% of budgets are diverted by insurgents (2023 audits). In distant locations, MGNREGA offers 50-60 days of work.

- c) Conflict and security: Ten to fifteen percent of rural projects in Manipur and Nagaland are disrupted by ethnic issues.

- d) Environmental vulnerabilities: According to FAO forecasts from 2024, climate impacts lower production by 10% to 15% annually.

- Government initiatives and challenges

The NESIDS and aspirational districts (Rs 25,000 crore, 2023-24) target gaps, with 100% rural electrification nearly achieved. Challenges include 15% fund leakage and AI/digital divides (HDR 2025 notes 30.7% HDI loss from inequality).

Organic farming in Sikkim boosted incomes 20% (2023).

- Recommendations for balanced development infrastructure push:

- a) Prioritize resilient roads and 5G for 50% rural connectivity by 2027.

- b) Economic diversification: Scale agro-MSMEs with Rs 5,000 crore incentives; shift 20% from jhum to sustainable models.

- c) Inclusive policies: Boost SHGs for 50% female land rights; ethnic forums for peace.

- d) Monitoring and equity: GIS-based MPI tracking; 75:25 rural fund allocation.

- e) Research and data: Annual PLFS/MPI updates for intra-state focus. (The contributor is a professor in the geography department of RGU, Rono Hills)