Monday Musing

[ Tongam Rina ]

Border towns are far and difficult to reach, and even seasoned travellers, ignorant yet accustomed to myriad tales, are kept wondering at the life experiences of the people who guard our borders.

Lada is one such place.

In East Kameng, soon to be in the newly declared Bichom district, bifurcated from East and West Kameng districts, Lada is one of the farthest border towns that had no road till two years back. Now it’s a town full of promises and potentials, thanks to the road.

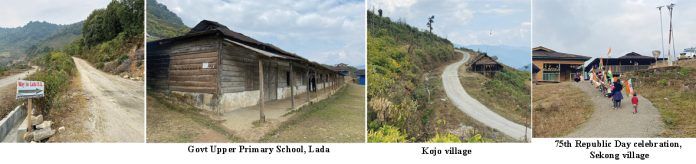

One evening, we sat down for a dinner consisting of rice, wild herbs, and mithun meat by a huge fireplace (which is typical of a Miji household) when I heard about a rice bag that fell from the sky and destroyed a part of the kitchen, barely missing the four people who were having tea inside. The mithun meat was leftover from the Republic Day celebration in Sekong village, where there was an inter-village sports festival to celebrate the day. National days are witness to the over-the-top celebrations, and in rural towns it goes a notch up. It was a feast in Sekong with two mithuns sacrificed on the auspicious day. It almost looked like a festival or a wedding.

The distance from Sekong to Lada is barely 60 kilometres, but it takes a good four hours of journey, and smaller cars can’t really negotiate the road that’s filled with pebbles on most of the stretches.

Four hours of bumpy, tiring, backbreaking journey in cold and grey weather, almost touching the clouds and fog and right at the base of the mountains within a few minutes because the road is built in such a way is an experience that is unpleasant and made me regret and wanting to go back. There we were, in a mini-truck that fortunately did not break down, unlike numerous others, including an ambulance, from Itanagar, carrying a dead body.

Lada, a small town with about 2,000 residents, is the heartland of the Sajolang or the Mijis. Home to Nyishis and Puroiks as well, it’s a comforting town surrounded by mysterious never-ending mountains and snow-clad peaks and several border roads being built at a formidable speed. It’s a typical border town that warms your heart in the cold weather with bright sun but leaves you wondering about the fate of those in need of medical help. There is a new hospital building, which is locked, they told me. Women go to Seppa or Bhalukpong to give birth – towns at least six hours away, on bad roads. Medical help is hours away and one can’t afford to have health emergency. Everyone dies, but in Lada people died from treatable illnesses before their time. Borders are harsh and unforgiving.

Almost everyone in Lada who can afford it has a home in distant towns like Itanagar, Bomdila, Nafra, Seppa, and Bhalukpong for their children’s education, or for better healthcare. But now there is a road at least, no matter how dangerous.

In border towns, one realises that roads not only connect but also bring dreams of a better tomorrow – where schools are closer, loved ones aren’t separated by long distances in pursuit of a brighter future, medical facilities are within reachable distance, and local produce can be easily sold. The people acknowledge the work done by the government, though it’s the duty of the government to do so and it should have been done decades earlier.

Listening to people share how roads have given them choices and dreams which were unthinkable all their lives makes you rethink the whole debate of being away from modern development, even though one wishes that it was done in a more environmentally sustainable way.

Lada is also where I met Dorjee Sangchoju, who documents his community’s rich oral history and culture. As someone who spent most of his life outside Lada, he told me that he returned for good because of the road.

Jeevan Sangchoju, his friend, is a cultural guide. He is not formally trained but, like many other indigenous youths, he deeply understands his community’s history and culture. He hopes to have a homestay for the tourists. Lada is abundant in its beauty and has the potential for cultural as well as adventure tourism.

I met so many like them, full of hope for a better future.

Sushila Sangchoju is one enterprising woman. She runs a shop, works part-time in a government office, and is a keen chronicler of the daily life of the people. She tells me how roads have made it better for everyone.

Meeting these young people, among many others, inspired me to rethink stereotyping young people as being disconnected from their roots and not having dream for the future.

Lada, where internet came few months ago, but where one can’t make calls and where walkie-talkies are still in use, is also a place of hope for a better future. Airtel 4G wakes up when everyone is asleep. Between 10 at night to five in the morning, the service works fast, but the rest of the time it’s intermittent, and therefore unreliable. They say that more mobile towers will be set up, but there is no definite timeline. As they say in Lada, sab hojayega future mei (Everything will work out).

It’s a place of learning and acceptance. We know that, even before the concept of remote work became widespread due to the recent pandemic, employees stationed in remote areas have been working from home in the headquarters or the state capital, only appearing when VIPs visit. The scenario is the same in Lada. It’s a place where finding a copier, or a Xerox machine, as we call it, can take an entire day, only to find that there’s no electricity during the day and the only office with a copier, the circle officer’s office, has run out of paper. I needed to copy some 40 pages, so I asked my host. After numerous voice messages and walkie-talkie conversations, it was finally decided that the school, or the circle office, might have a copier. It was agreed that the school was the best option because the teachers would help. The teachers were busy preparing the students for exams. Since it was a Saturday, government offices were closed, but it was midday meal day for students. I ended up having tea and spending time in the smoky kitchen where the meal was being cooked. Saturdays are the only days when midday meals are served, and I watched as children lined up to enjoy their meal.

Those who didn’t bring plates and spoons had to wait for their friends to finish eating, so they could use theirs. Most students were underdressed for the cold weather. Not everyone can afford warm clothes, the teachers say. I regretted immediately for asking a stupid question. Many students from nearby villages stay with relatives in Lada, but some from nearby villages without roads walk up to three hours a day to reach the school, the teachers told me. The dilapidated school, established in 1986, is almost on the verge of collapse, and it looked like it had never been repaired once. There are 140 students and eight teachers. The nursery was well lit though.

It had no paper, nor a copier.

Summer will be yet another time when Lada will revert to its pre-road days due to the terrain and poor engineering. The place still lacks public transport. Unless you have your own vehicle, you can never be sure when the private Sumo taxis are coming next. Sometimes it takes up to a week to find a vehicle to Seppa, the district headquarters. It’s not that far from Seppa, but they say that the less-than-perfect condition of the road makes the distance even farther. Moreover, regardless of where you get off, you still must pay the full fare for the destination.

The rice bag that fell from the sky was government-supplied rice via the Indian defence force deployed by the government. Although Lada isn’t sprawling, it’s not so small that it would miss the landing ground, which is in the middle of the town and is a big open space. Yet, some pilots in a hurry chose to drop the rice bags on top of a house instead of airdropping it on the designated ground, destroying the house and narrowly missing the people inside.

As they shared the story, they laughed nervously, because such incidents have happened so many times. But those days are in the past; the road has come to Lada, they say.