TribalBookworms

[Dr Doyir Ete Taipodia]

Have you ever heard of socks as a way to tell generational differences? It’s true! Recently, during a fascinating conversation with my friend and co-writer, we caught an amusing trend between Gen Z and Millennials. These two generations can be identified (as claimed by some) by the length of their socks — Gen Z prefers long socks, while Millennials stick to ankle-length ones! Initially, I found this absurd, but the more I thought about it, the more it made sense. After all, history is full of quirky standards used to judge beauty, class, fashion, and even creative writing. If socks can be used as markers of generational differences, why not eyebrows? After all, brows have been indicators of class for centuries, much like how we use highbrow, middlebrow, and lowbrow to distinguish between different types of literature.

The concept of ‘brows’ originated in the United States in the 19th century to refer to the physical appearance of a high forehead, which was thought to be a sign of brilliance, or superior intellectual faculty. Although proven to be scientifically false, its use as a metaphor for sophisticated or serious cultural pursuits lingered on. In art and literature, for instance, the divisions of highbrow, middlebrow and lowbrow began to be used in common parlance to refer to different standards of works. Thus, highbrow connotes cultural elitism or refined taste. In literary discussions, highbrow in literature refers to literary works that are considered sophisticated, intellectual and of high standard. It often refers to classical or canonical works. However, over the years it also suggests an elitism that is out of touch with popular or everyday culture. As opposed to this is the lowbrow, often considered light, unsophisticated and unserious yet offers a pleasurable read. Normally, pulp fiction, racy romances, or sensational writings fall into this category whose main aim is simple gratification. Middlebrow literature strikes a balance between the two. It includes works that are intellectually insightful and at the same time entertaining, appealing to both the intellect and the heart. It has broader mass appeal, is accessible and often makes it to the bestsellers list. Middlebrow is what we understand to be the popular culture. I therefore love books from such ‘in-between space’, a space that challenges the mind and touches the heart.

However, these categories are not rigid; they are not chiselled in stone. These are fluid and context-dependent, and it is possible to move across these categories depending on certain factors. One popular example is the Harry Potter series, which began as a popular culture and is today a highbrow studied by scholars for its themes, literary qualities and cultural impact. The Hunger Games is another such work that, like Harry Potter, has not only been made into blockbuster franchises but also studied for its rich themes and social commentary. Novelists Jane Austen and Charles Dickens began as middlebrow,and are today acknowledged classics in their own right. Thus, these examples show how an author begins with simple stories and poems before honing their skills and producing more rich artistic creations. It is possible to move beyond labels with discipline and determination.

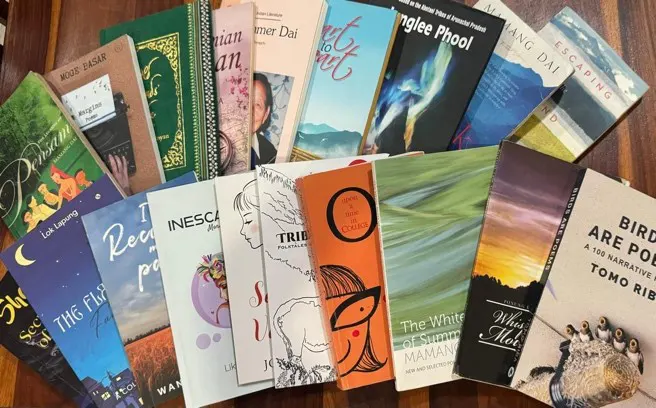

While no one can definitively set the rules of what constitutes ‘standard’ or ‘non-standard’ writing, a benchmark is necessary to measure the worth of books. The foundation of a rich literary tradition depends on this. Thus, I revisit many of the literary works currently circulating in Arunachal Pradesh to stress why we need to raise our bar and aspire to higher standards. For instance, a few books I recently came across are painfully deficient in structure and formatting. Many lack an ISBN or any unique identifier for books, nor do they have a contents page. The ISBN helps track and categorise publications, and its absence spoils the first impression, making the book seem less professional. The lack of a contents page or titles for individual poems adds to the confusion, making navigation of contents cumbersome and may lead the reader astray. In such cases, referencing specific poems and citations becomes ambiguous, as it’s harder to point to a particular work within the volume. This also creates difficulties for other readers trying to verify references. Willy-nilly, there are standard conventions one needs to adhere to, or else the work may not be taken seriously and it can affect the meaningful engagement with literary texts.

I will refer to some specific works to point out certain omissions, which I understand may have been inadvertently committed. I also do it so that I am not accused of making gross generalisations in my observations or claims. Two recent books in the literary circles, Tribal Echoes: Folktales from Arunachal Pradesh and Inescapable: More than Just a Word, are missing identifiers like an ISBN. Tribal Echoes is a beautifully written collection of folktales with lucid language and well-structured stories. The concise blurb was a plus point to the overall presentation of the book. However, the book leaves me curious about the curation process, especially as it features stories from various tribes in our state. A background on this would have made for a rich introduction to the book. On the other hand, Inescapable: More Than Just a Word – a collection of poems – is a valiant attempt at capturing raw emotions. However, as the author states, “to look for meaning is like a puzzle,” many poems fall short of challenging the reader. The thoughts are honest with sensitive emotions suggesting rich potential for the poet. Another book, Sanity in Vanity, captures the Gen Z’s anxiety as they juggle to make life in these uncertain times. However, the lack of titles for the poems, along with the overall sparseness of the volume, is a limitation. The poems are sometimes brief — just two or four lines — yet far from the depth of a Haiku or a traditional Quatrain. While the work reflects a young poet’s visceral emotions while conveying a positive message, it lacks the granularity of language and nuanced expression that poetry demands. I hope the poet will strive for this depth in the future. I Recalled My Past, from a promising poet, does not deliver in terms of his capability. The collection is again without a content page and titles for poems. At first glance, the book appears voluminous, but this impression fades once you begin reading. Many pages contain only one, two, or four lines of poetry, often featuring clichéd phrases commonly spoken. Additionally, the blurb requires revision for language and grammar. Knowing the poet personally and recognising his brilliant potential, I would suggest he write mostly in the language he is most comfortable with. I must concede that the choice of language is personal, and writing bilingual works deserves applause. However, it must be done with diligence and keeping in mind the specific requirements of each language.

I take this liberty of advising, cautioning, and even critiquing knowing very well that these may sound unpalatable. I do hope it is taken with the right spirit and positivity. These observations are to encourage young and aspiring writers to hone their creativity but be diligent at the same time. Given the growing interest in literature from Arunachal, worthy works will definitely strike a note with the readers. One does look forward to the bourgeoning of literature -both highbrow and middlebrow ultimately contributing to the literary tradition of the state. (Dr Doyir Ete Taipodia is Assistant Professor, English Department, RGU. She is also a member of the APLS and Din Din Club.)