[ Nongthombam Devachandra ]

The ‘land of dawn-lit mountains’, Arunachal Pradesh, the eastern most state that receives the first ray of the sun is located between 26.28° N and 29.30° N latitude and 91.20° E and 97.30° E longitude. It covers an area of 83,743 km2, making it the largest state in the Northeast region. It was renamed from NEFA while attaining the status of union territory in 1972, and became a full-fledged state on 20 February, 1987.

It falls in the Indo-Himalayan-Myanmar-Indonesia belt that houses numerous endemic flora and fauna. It is quite interesting that, now and then, new species of plant, ape, amphibian and reptile are regularly discovered in this state. The state is also known for its varied climatic zones – Alpine in the north (border areas with China-Tibet), temperate in the west (bordering Bhutan), and tropical-subtropical in east and south (bordering Myanmar, Assam, and Nagaland).

When we are discussing about the state, it would be appropriate to reiterate what forest is to life. Jivan: ‘Ji’ = life; ‘van’ = forest. It speaks volumes about what forests are in our life and human civilization.

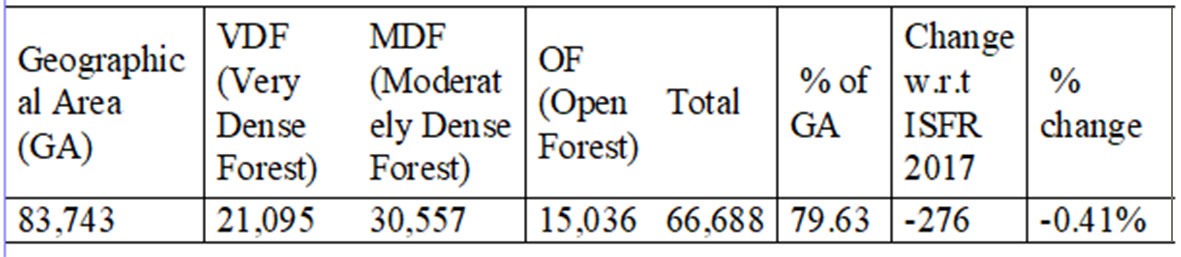

The state stands second both in terms of absolute area under forest (first being Madhya Pradesh with 77,414 km2) as well as percentage of area under forest with the total geographical area (first being Mizoram, 85.41 percent). As per the India State of Forest Report-2019 (ISFR-2019), the absolute area under forest in the state is 66,687.78 km2 that comes to 79.63 percent of the state’s geographical area.

For the first time, an assessment of biodiversity for all states and union territories was conducted. It was found that Arunachal Pradesh has the maximum biodiversity of species with respect to trees, shrubs and herbs in the country, followed by Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. This would include citrus species (lime, lemon, pummelo and oranges), musa species, orchids, etc.

Promoting horticulture should never get in the way of conserving forests. When better is possible, good is not enough. It may be difficult yet possible to have a conjunctive approach of promoting horticulture without undermining forest coverage. There are numerous multipurpose tree species, even the fruit crops which are often incorporated in forestry programmes. The declaration of the year 2021 as the International Year of Fruits and Vegetables by the UNGA gives a louder message to promote horticulture crops (fruits, vegetables, MAPs, flowers, plantation, spices, etc), especially local, underutilized, nutritious crop species.

The ISFR-2019 revealed an increase of 5,188 square kilometres of forest and tree cover across the country compared to the ISFR-2017; however, the Northeast in general and Arunachal Pradesh in particular continues to lose forests when compared to ISFR-2017 and preceding reports. Forest coverage is decreasing in the state by 276 sq kms (Table 1).

Table 1: Status of forest cover in Arunachal Pradesh (ISFR-2019):

Before deriving any conclusion, it would be wise to understand the complexity of the Forest Acts in terms of their interpretation and implication, an illustration of which may be cited as below:

In a landmark decision by the Sri Narendra Modi that on 23 November, 2017 the central government amended the Indian Forest Act, 1927, ensuring the legal classification of bamboo as ‘no longer be treated as a tree’ if grown outside reserved forest areas. It will always remain an unanswered doubt to young minds why Bambusa species belonging to Poaceae (Syn Gamineae) as every taxonomist knows, still continues to be ‘tree’ if grown in reserved forest areas as once classified by British India? It is high time that the learned IFSs in closer consultation with horticulture professionals of the state came up with certain thoughtful proposals to amend the related Forest Acts to address the issues of cultivating desired perennial horticultural crops (say fruit-bearing trees) by the people of the state who ‘own’ the hills and mountains as per their traditional and customary systems. There may be proposals wherein selected fruit trees are consciously and purposefully included in the afforestation programmes. This may give an impetus to motivate villagers to retain and maintain greenery as well as enable to enhance their farm earning. An important concern is that the effort to increase acreage under horticulture crops shall never be a point of confrontation with forest’s coverage issues. They are closely entangled as fruit crops are almost always cultivated in hills in the state.

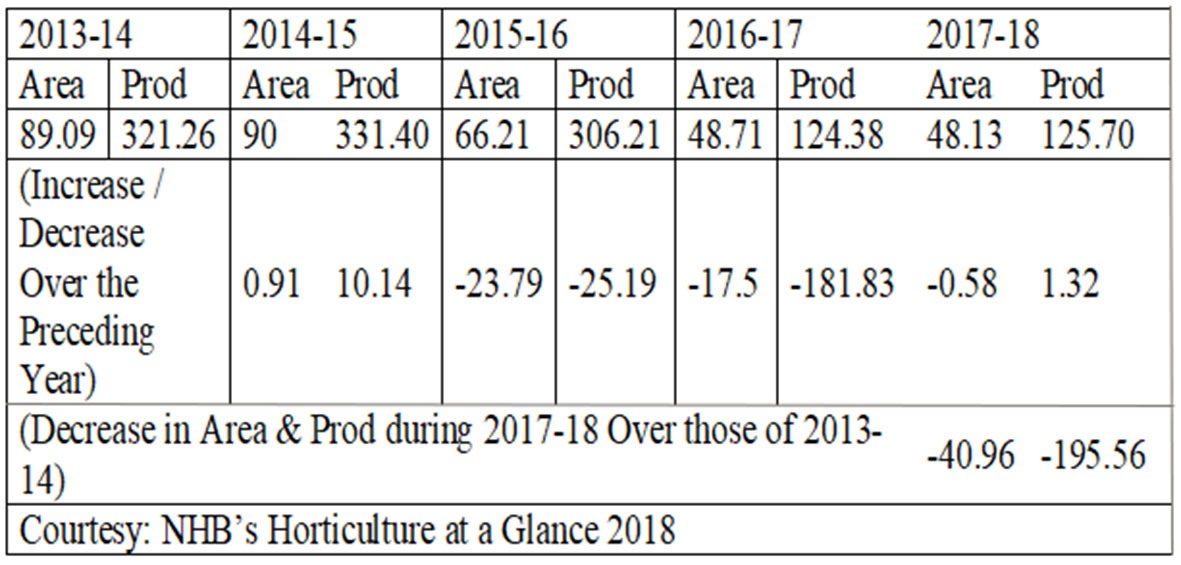

On the other hand, it is pertinent to understand the land ownership systems, and the prevailing practices in promoting horticulture. The village communities own the hills and the mountains in the state. Unlike in the other states, we do not have ‘forest dwellers’ in the state. While cultivating perennial fruit crops (either vines or woody trees), jungle cleaning is practised for layout and orchard establishment. Once the fruit trees develop, the greenery coverage remains for more than 30-50 years, sometimes upto 100 years. Let us see the area (and production) of fruit crops in the state (Table 2) for the last five years as recorded in the National Horticulture Board.

Table 2: Area & production of fruit crops in Arunachal Pradesh for the last five years:

[Area in ‘000 Ha & production in ‘000 mt]

Now, the real issue emerges. It had been an argument or notion that a decrease in the forest ‘might have been’ on account of increase in the acreage under horticulture crops, especially fruits whose cultivation needs site preparation. This demands conjunctive approaches by the department of forests & environment, the department of agriculture and the department of horticulture in a more holistic tandem, keeping the larger interest of Arunachal Pradesh at the centre.

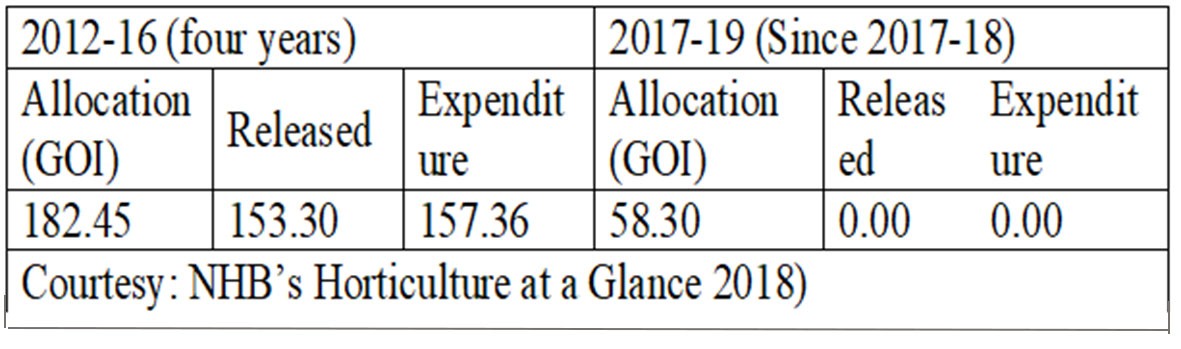

It is true that the department of horticulture is struggling hard to implement various schemes of the National Horticulture Board. In spite of the efforts, an allocated fund of Rs 58.30 crores of NHB could not be released/expended (Table 3).

Table 3: State-wise allocations, releases & expenditure under National Horticulture Mission for Northeast & Himalayan states:

(Rs in crore)

It is a challenge for agri-allied professionals to extend advisories for large-scale commercial ventures in horticulture sectors due various limitations. Some of the prominent ones may be enlisted as hereunder:

- Absence of medium- to large-scale nurseries that raise (not trading) quality planting materials as required by the farmers/growers in sufficient quantity at affordable prices.

- Those who possess resources like arable lands, capital and manpower have no or least interest in venturing into agri-allied business on a commercial scale. On the contrary, enthusiastic agripreneurs who desire to undertake agri-allied activities as business ventures often do not have these resources.

- Difficult physical terrain of the states. The site of garden/orchard/estate is often not connected conveniently (no motorable roads) with nearby towns. It’s heartening to reiterate that many orchards in the state are still connected with villages with bamboo-cane-GI wire bridges. Therefore, the farmers find it too difficult to carry in every essential farm inputs as well as their harvested produces – gingers, turmeric, large cardamoms, oranges, etc.

- Absence of successful sustainable buying-selling practices or contract farming model. Neither the buyers nor the farmers have satisfactory experience and history of being partners as ‘agreed-upon’. The APMC needs to be empowered with sufficient manpower and capital.

- Absence of well-organized supply chain management (SCM) for horticulture commodities in the state. Different stakeholders in a typical SCM exist in the state. However, there are various missing links. Nurseries are raising planting materials which are least preferred by the farmers at that point of time. The transporters (as they claim) do not bother much what they are carrying – stones or santras, sand or seedlings, etc. Carriers are not customized. They usually charge similar fares, pile/load things up with least care, etc.

- Yet to implement crop insurance in the state.

- Limited credit linkage for the farming activities.

Suggested remedies and mitigating measures:

- Few of the progressive farmers and fruit growers may take up nurseries as agribusiness venture. They could concentrate on raising seedlings of seasonal vegetables, including those of locally-preferred vegetables, saplings of fruits, agro-forestry. While seedlings of vegetables and flowers and saplings of agro-forestry crops are raised sexually through seeds, locally preferred vegetables, ornamental foliages are raised through vegetatively either cuttings, layering or suckers. For fruit crops raising of rootstocks and sale of it or/and raising of saplings through budding /grafting. Fruit crops like litchi, guava are commercially propagated through air-layering (kolom on branches). On the one hand, their earning would increase manifold. On the other hand, at least authenticity of the ‘true-to-type’ of the desired variety of the crop can be ensured. It would be worthwhile to mention that when planting materials are procured from other far-off places, chance is very high of getting introduced soil borne pathogens, nematodes and weed seeds into the state.

- With due consideration of the existing land tenure system of the state, we may propose to formulate a ‘legally acceptable leased system’ for the landowner and the tenants (enthusiastic agripreneurs). Consent of the gaon burahs may also be incorporated to avoid social entangling in future as agri-allied ventures are of long duration projects (3-15 years). Apprehension in the minds of prospective agripreneurs is, ‘what if the landowner asks to abandon or vacate the land once the venture kicks off? We all do not have an affirmative answer for this worry. Therefore, a legally acceptable as well as socially acknowledged land leasing system would open up opportunities for emerging agripreneurs.

- It is obvious that we cannot change the terrain. We cannot alter where we are located on the globe. Therefore, GLOCAL (Global approaches to local condition) should be a practical strategy. It would be interesting to acknowledge the prevailing farming practices. Let there be scale up (instead of changing the crop or activity or introducing a new one); inclusion of improved variety (of the already familiar crop); niche farming (guiding for high value low volume crops like medicinal and aromatic plants). An approach may be to adopt and incorporate some of the appropriate post-harvest management (PHM) practices like harvesting at appropriate stage, following harvesting indices; establishing small-scale primary processing units at the site of cultivation, ie, sorting, grading, drying, packing, crude juice extraction/pulping, etc, that can be operated with small generator sets. Wherever the number of farmers is more and area under cultivation is quite large, there can be collective efforts for installing ropeways for carrying up inputs or carrying down the produces. With the support from government line departments or as collective efforts amongst farmers, solar panels can be installed at farm or orchard located at a far-flung site for lighting as well as operating few processing machineries.

- “Jab dudh se muh jalta hain toh lassi bhi phukr pita hain.” It’s an old adage. The elder generations have burnt their fingers in a few of the ‘good intended’ model of contract farming or buyback arrangement. A different approach may be to insist for ‘participatory contract farming – PCF’. In addition to the contract agreements as in APMC’s contract farming model, the following is envisioned in PCF:

- The contract firm or the agency ought to engage itself in production of the same variety and crop in an area not smaller than an acre (3 bigha or approximately 4,000 sq mtrs). This would drive away the apprehensions amongst the contract farmers that what they are practicing is appropriate or not. Because they would have no reason to deviate from the agreed package of practices – land preparation, spacing, seed rate, quality seeds or planting materials, types-dose-methods of applying manures, plant protection measures, pre- and post harvest-operations, harvesting index, etc. On the other hand, the firm shall not have to dictate over the quality of the produce as they would be harvesting what the farmers are harvesting.

- Farmers may be motivated to come together as farmers’ club, farmers’ society, FPOs that can be upgraded to FPCs in subsequent years.

- Farmers would be allowed to raise their own nurseries to ensure timely, sufficient quantity of good quality seeds or planting materials.

- Farmers manage their inputs and farm machineries in closer consultation with the contract firm through the custom hiring centre-cum-supply of inputs.

- Under any circumstances, the kebangs and GBs should be involved for any such contract farming matter. This would ensure sorting of any complications of implementation. The elders in any village have many experiences to share. At least they need to be informed. This would benefit both the producers and the firm.

- In a typical supply chain management of fruits and vegetables, farmers, auctioneer, agents, wholesalers, cart vendors, traditional retailers and consumers as stakeholders. This chain can be presented extensively by inclusions of more stakeholders like nurserymen, agri-allied input dealers, horticulturists/consultants, middlemen, fruit traders, wholesalers, retailers, processing units, agri-exporters, consumers.

However, keen observation of prevailing supply chain of any horticultural produce reveals the existence or involvement of numerous unconventional stakeholders. They are called so because their ‘core’ business is something else. Their sustenance is not depending upon agri supply chain, but the sustenance of agri supply chain depends on these stakeholders; they act as enablers, making the chain stronger and more efficient, benefitting stakeholders at the farthest ends: suppliers of the suppliers of the suppliers as well as customers of the customers of the customers (including the producers (farmers) and consumers).

Therefore, unconventional stakeholders in an improved agri supply chain would include: Bank/financial institutions; transporters-travel agencies (including passenger vehicles); doctors/physicians; chartered accountants – project consultants; police/traffic/security forces; journalists/media/publishers; tools and machinery manufacturers/fabrication units; artificial intelligence sensor-based fruit harvester; electronic-based, drone-based practices; social/civil organizations; courier service provider (India Post and private couriers); road construction agency etc.

- The insurance sector is yet to get popularity. Insurance of the farmers need to be popularized. The government owned Agricultural Insurance Company of India Ltd (AICIL) and many general insurance companies are implementing numerous agricultural insurance including PMFBY in other states. The directorates of agriculture, horticulture, veterinary and fishery may take up the matter on priority for the benefit of the farming community. This would even encourage financial institutions for larger credit linkage.

- Banks and financial institutions are always looking to finance bankable projects and also assist creditworthy farmers. A state-specific land tenure system and issuance of appropriate land possessing certificates would go a long way in encouraging financiers. To formulate a mutually acceptable and legally feasible mechanism involving GBs and kebang for credit linkage of farmers in the respective villages in a similar model of village development board (VDB) of Nagaland.

Conclusion

Horticulture can be promoted not only by professionals, institutions and department dealing with it but also in close liaison with other departments that are associated with horticulture directly or indirectly. If essential, initiatives may be taken up to amend laws that are coming in the way but with a holistic approach, keeping the objective of including Arunachal Pradesh in the horticulture map of the country. The state has the required potential to carve its position in kiwi, strawberry, blueberry, Arunachal orange (GI), spices (ginger, turmeric, black pepper, large cardamom), MAPs, orchids, wild endemic flowers and foliages, and special teas. The contents may serve as food of thought for whomsoever concerned. [Nongthombam Devachandra is Assistant Professor, Fruit Science, College of Horticulture & Forestry, Pasighat)