[ Dejna Daulagupu ]

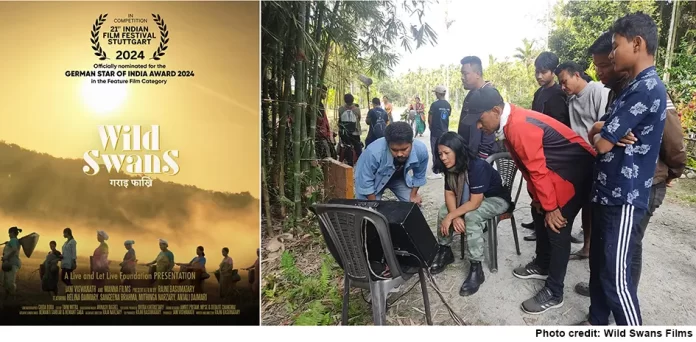

Social science researchers especially, of the ‘anthropologist’ kind more often than not end up being used as characters in thriller-horror movies (see Altered States (1980), The exorcism of Emily Rose (2005), Midsommar (2019), Aamis (2019) or in films with ‘teachable’ plots, naturally ending up in those situations because of their ‘exotic’ interests (Weston et al,2015). Gorai Phakhri or Wild Swans, directed by Rajni Basumatary is a welcome exception to this trope. Having done one round of screenings around the world, the film has won many accolades including the title of Best Indian Language film at the 29th Kolkata International Film Festival (KIFF) and an official selection at the 42nd Vancouver International Film Festival.

Preeti, who is the main protagonist of the film, is a doctoral student at Gauhati University with her thesis focused on Boro women. As the film picks pace, Preeti, who has just received news of a received grant, prepares to leave for fieldwork in her ancestral village in Bodoland Territorial Region (BTR) – her thesis dealing with Boro women’s experience. Having grown up in an urban upper middle class Boro family, she leaves for the field with many presumptions about rural women, proud about the relative equality women enjoy in the Northeast region in comparison to peninsular India. Gorai Phakhri is essentially a window into Preeti’s fieldwork in BTR where she navigates her own precarious position as an insider-outsider as she gets increasingly embroiled in the lives of the women of the village.

The main focus of the film is on the ongoing negotiations between the Boro community and their violent and conflict-ridden realities. Through this film, Basumatary portrays the experiences of the many Boro women – young, old, rich and poor, whose quiet struggles get drowned in the ocean of stories coming out of this violence-stricken context. Interspersed with the paddy fields and the eastern Himalayan hills are the underlying tensions brewing in the village. The stories coming out of this one Boro village echoes the realities of several frontier communities across the Indian state and especially, sheds light on the otherwise untold experiences of women who doubly suffer under patriarchy even whilst surviving a war. Basumatary is intentional and nuanced in the way she carries the stories of the women in her film, addressing the intersectional diversity in women’s experiences within the community. Another aspect that sets the film apart is its generous focus on Preeti’s negotiations as an anthropological field researcher.

Basumatary’s collaboration with an actual anthropologist is very apparent in the script which frequently delves into the methodological intricacies of an ethnographic fieldwork through Preeti’s character. This film could very well be screened supplementarily with a methodology module in social science departments. Anthropologist Dolly Kikon who also makes a guest appearance in the movie, collaborated in editing the script and Preeti’s character in the film is written, very visibly informed by Kikon’s contribution. As a researcher conducting fieldwork, Preeti embodies the trepidations and anxieties of a field researcher. Gorai Phakhri is as much a story about the women of BTR as it is about Preeti’s research journey as an anthropologist.

From the moment Preeti gets off her bus at the village, the film promises an honest engagement with the character’s ‘researcher’ self as well. Minute details throughout the movie such as the scene where Preeti asks for consent before clicking a picture of a farmer, ground the film in ethnographic research methodology. Often stumbling into conversations and even feuds among friends, Preeti is a listener and observer more than a typical protagonist who behaves like a saviour in the village. Especially, her research journey within the larger plot of the film also complicates a central anthropological debate about the insider/outsider. Gorai Phakhri brilliantly showcases the challenges of being a native anthropologist. As a Boro researcher in a Boro village, it becomes apparent to Preeti that her fiancé (who also hails from the same community) is disdainful towards the villagers and refers to them as “these people.” He also reminds Preeti to stay detached, avoid mingling with the ‘villagers,’ and return home with only the “data” needed for her study. His voice over the phone is commanding. As Preeti begins to see how even women that she had once thought were liberated and free, are trapped in patriarchal relationships, she starts to notice the skewness in her own relationship with her fiancé.

In the village, Preeti befriends a group of women who she shares most of her time with. She accompanies them in their endless work, across paddy fields, streams full of fish and foraging grounds where she comes across their stories. Gaodang, a mother of two is the wife of an army sipahi, Malothi- Mainao’s mother is an independent woman who lives alone and on her own terms. Anondi is an Assamese woman married to her Bodo husband, while Bimuli struggles to live with her alcoholic and abusive husband. Through the life stories of these women, the audience learns how patriarchy can be insidious and experienced in horrific ways during an armed conflict. While Mainao and Gaodang’s friendship is afflicted by the burden of their husband’s alliances to two opposing armed factions (the former’s late husband being a member of a Bodo armed group and the latter being the wife of a soldier in the Indian armed forces), Malothi’s tragic experience of gang-rape by the Indian army and the ensuing humiliation at the hands of her Zamindar husband brings to light instances of sexual crime and shame borne by women in a patriarchal society in an armed conflict situation. This account echoes the harrowing everyday reality of many women in conflict zones across the world whose bodies become the ground for sexual violence. Malothi’s choice of leaving her marital home to start life anew represents the trauma and the continuing journey of healing and reconciliation for communities in militarised societies across Northeast India. Through Malothi’s character, the audience is drawn towards showing empathy towards survivors of sexual violence and also engaging with issues of impunity and patriarchy in conflict societies.

This film also weaves in an intergenerational account of women fighting patriarchy. The story of Gaodang’s teenage daughter being sexually harassed online by an older man from the same village captures the continuity of sexual harassment and bullying in the digital age as young girls must once again deal with new forms of challenges. Gorai Phakhri highlights the universal phenomenon of conflating the policing of women’s bodies with ‘protecting’ culture in a powerful scene where a poster is circulated shaming the wearing of clothes other than the traditional dokhona (Boro traditional outfit for women). The script subtly encompasses the struggles of women without preaching or overtly making big statements. Basumatary succinctly draws our attention to women’s experiences in a patriarchal society and how some of them become enforcers of patriarchy. This film centres women where men only appear through their voices or images. The theme of food provisioning is intelligently interfused throughout the film to highlight women’s contribution in feeding the household. Women fish, plough, cook, serve, fight, and also sing and dance together. Women feed and care for the community yet one of the female protagonists exclaims, “even though women do all the work, the money from selling grains goes into the men’s pockets.”

The anthropological gaze in this film is about indigenous women’s solidarity and a celebration of friendship in the midst of hardship and violence. The film did a good job of condensing a researcher’s experience into a 3 hour stretch. A fieldwork is much more extensive than the scope of the film would have allowed. It is sometimes a stretch of quiet days of wandering and exhaustion interspersed with days filled with a rush of events and then a much wider spectrum of emotions caused by the fieldwork experience. And a long period of preparation for the fieldwork which is often reworked and upturned by what the field reveals itself to be later. While the ending feels a little hurried, the film does the job of portraying the beauty and violence of life in rural BTR without shying from addressing internal hypocrisies while speaking of gender experiences.

The concluding scene of the film takes place during Bwisagu – the harvest celebration of Boro people. It features the women cooking in the kitchen as Preeti packs her bags and books to leave the village. The food, laughter, and bonding leaves the viewer feeling joy and brightness. Gorai Phakhri directed by Rajni Basumatary makes a huge stride for indigenous Indian film making in Northeast India. It heralds a new generation of films that deeply engages with the distinctive socio-political landscape of Northeast India that centres indigenous peoples’ lives and their worlds. For those from this part of the world, this movie is a step towards reclaiming agency and voice on the global stage of art, craft, and storytelling.

(The writer is a researcher working at the North Eastern Social Research Centre, Guwahati, Assam. Her research interests include themes spanning across agro-ecology, gender, land and indigenous issues in North East India.)