Tribal book worms

[ Dr Bompi Riba ]

Of late, social media platforms such as Facebook and X went berserk with frenzied opinions on former Miss Arunachal Tengam Celine Koyu’s congratu-latory post to the reigning Femina Miss India Arunachal Pradesh because of her claim regarding the “school renovation project” and also her assertion of not allowing anyone to take the credit for that initiation. The carnival-like situation for shamers and trolls who masqueraded as just voices feasted on the opportunity to mortify her without really caring about how it could affect her mental health. This episode reminded me of a famous essay, titled ‘Shooting an Elephant’ by George Orwell. It was published in 1936. Though the essay is concerned primarily with the dilemma of a colonial officer who disliked colonialism, it performed his role as expected of him by his compatriots and the colonised Burmese population. My focus is on the tamed elephant that was shot unnecessarily. Since it was a domesticated animal, it was expected to behave well. In other words, the normative behaviour for the elephant was not to go on a rampage in a public space. Unfortunately, it went temporarily wild because of ‘musth’ and acted just the opposite of its normative behaviour, as a result of which it costs it its life. Interestingly, when it comes to beauty pageants, the title holders are also expected to behave in a certain way that is honourable. However, while the society expects them to be humble and engage in selfless services on humanitarian ground, it becomes unsettling for the same society to have such role models, who for the sake of their dignity and self-esteem challenge the very institution that supposedly “made them” with statements that refute their integrity.

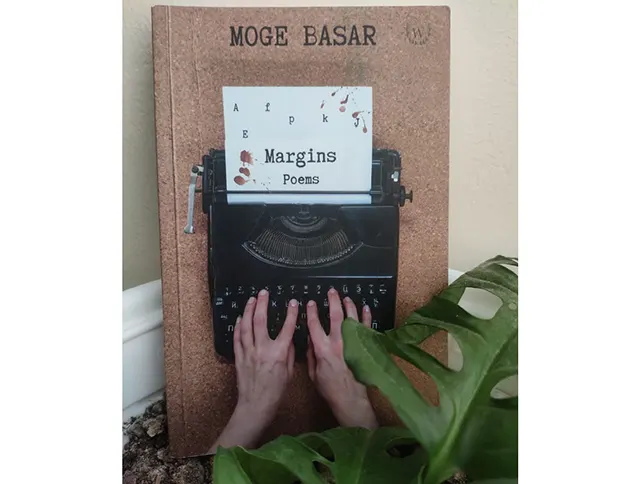

While young contestants participating in such events look forward to explore their ‘self’, pageants also generate identities which could be performative in nature. These created identities either align or clash with the gender essential roles designed by the society, which mostly practices patriarchy. At times the tussle between these identities also lead to one experiencing a state of existential crisis. Interestingly, a young poet who deals with the complexities of the ‘self’ in his first book of poem, titled Margins: Poems, published quietly without any promotion in the year 2022, is Moge Basar from Leparada district. The ‘I’ in all of his poems remains an anonymous, nameless subject. He seems to be quite conscious of his surroundings and then by observing and also judging, he defines his self. According to Kant, the observations made by the subject concerned become representations that contribute towards the perception of the ‘I’. Every observation of the poet also channels through his ‘I’. However, unlike Rousseau, who presents himself as himself without any inhibitions, the poet seems to hide behind the many ambiguous ‘I’ in his poems. Unlike Rousseau, who inadvertently claims, “I may be no better… but at least I am different,” Moge’s poems have a first person ‘I’ as the speaker, and despite that, it distances the readers from the poet’s real personality. The individual ‘I’ in the poet seems to be exclusive, and so, despite the various concerns raised in the poems, it is difficult for the readers to frame a unified ‘I’ as a wholesome personality. Despite subtly attacking at the traditions that have not permitted the free growth of the ‘self’, he seems to come to terms with his ‘self’ in isolation though he longs for companions too. The ‘I’ does not seem to be self-contained. It struggles and develops its sense of ‘self’ by observing, analysing and logically arriving at one’s perspective to assert one’s self. For instance, in the poem ‘A Plea’, his vulnerability is revealed when he expresses his need of the approval of the other for ascertaining his self.

The speaker of his poems often displays a distinct urban personality living segmented lives in a metropolitan city. One of the characteristics of a city is that it is a place where individuals from socially, culturally, economically, and even racially diverse backgrounds make their permanent settlement there. A city has a dense heterogeneous population, as a result of which there exists multiple segregations based on differences arising out of social status, financial status, ethnic background, colour, food habits, preferences, etc. As opposed to a close-knit society found mostly in rural settings, there is a relatively weak or no kinship among neighbours in cities. Their interactions with people are usually superficial, impersonal, segmental and transitory. This explains the reserved anonymity of the transitory urbanites which is the main characteristic feature of the speaker in Moge’s poems which frequently deal with mundane activities of a city dweller. For instance, under the section ‘Airport’, the poems, such as ‘Raillery and ‘Taboo’, exhibit the secondary nature of the poet’s contacts with people at the airport. Mundane activities, such as casual talks with passengers waiting for their flights, a chance stealing of glance with strangers, and the organic response of restraining oneself from forbidden intimacy are some of the key highlights. Interestingly, even in the mindscape, the speaker holds inhibitions upon the idea of the possibility of such chance meetings as inceptions of intimate relationships. This conveys the internalising of the social codes of behaviour that is attuned to morality. In fact, the poem Chance Meeting’ manifests forbidden love. This is one of the first poems in the collection that hints towards homo-erotic encounters. This forbidden intimacy could also be interpreted as maladies of an urban society. It can be an extramarital affair, a fling, or a casual one-night stand.

It can be presumed that the poet in his absorption of seeking his ‘self’ disassociates himself from the fictional ‘I’ but is involved more in rationally processing his conscious mind. It is as if through these fictional ‘I’s, there is a gratification of the forbidden acts which one would avoid consciously. In other words, it seems that these varied forms of ‘I’ are in fact part of the author’s consciousness which he deliberately detaches in order to avoid risking being exposed as vulnerable. It is as if the poet has used art to explore his unconscious mind. Thus, it hints towards how one’s repressed self and sexuality get liberated through art. His poems propose the idea that ‘I’ is supposed to be rational and free but it seems to be under the pressure of conforming to the ideologies propounded by the society. So, without being too blunt, he subtly attacks the society. It is as if through observation of the others that his ‘I’ becomes more pronounced. Though these experiences are diverse, they are related to his thinking self and the representations of these ‘selves’, whether absurd, abstract or even primitive, are based either on intuition or observations.

It has been mentioned above that the subject of Moge’s poems is an anonymous ‘I’. For readers like me, who could not overlook the fact that the poet is a tribal man, the unexplored trajectory of the challenges of the tribal ‘I’ in urban settings in his poems was a major disappointment. Probably, the poet did not want to be trapped in a fixed identity. That’s why he must have explored the more universal human subject and his perennial challenges. One can also not overlook the fact that his ‘I’ calls home a trap where he experiences a denial of the self. Interestingly, it is in distant places, far removed from the various dogmas of the society that he belongs to, where he really feels at home with himself. As in the poem, ‘View from an Airplane’, while departing from an anonymous city, the speaker talks about finding a part of him there which he never realised before. As mentioned above, the anonymity in the cities comes with the added privilege of being free as you are not accountable to your kith, kin and neighbours. Such freedom also permits you to grow individually. He proposes that in the quest for one’s self, the inward journey is what matters. And for a lyric poet like him, the assertion of ‘I’ is gratified through creative compositions. He writes in his poem, “I only leave blankpages/in my wake/and the ones I fill/are only a rambling/of the eternal lyric I”. Such a beautiful line!

In conclusion, my verdict on this book is that it was like a breath of fresh air. While there still is some room for growth, the poet has exhibited remarkable potentiality which did not go unnoticed. He had delved into the nuances of the complex subject ‘I’, and that needs to be appreciated. Hope he does not stop writing. (Dr Bompi Riba is Assistant Professor, English Department, Rajiv Gandhi University. She is also a member of the APLS and Din Din Club.)