TribalBookworms

[ Dr Doyir Ete ]

I had a basic understanding of Donyi Polo, having grown up in a family that wasn’t overtly religious. Yet, certain aspects of our lives were intricately intertwined with practices and rituals, with Mopin holding a central place. Mopin involves a wide array of rituals, each rich in tradition, and being a witness to them every year while growing up, I assumed I was familiar with their meanings. However, over the years, I began to question the deeper significance behind these practices, much like many others in different tribes and societies who share a curiosity and a need to understand what forms the core of their identity. I’ll admit, like many others, I once thought tribal faiths, such as those of the Tani tribes, revolved solely around Donyi-Polo – the sun and moon – and a handful of deities. To me, they seemed simple, grounded in nature worship, and lacking the depth we often associate with grander philosophies or established religions. But I was wrong.

Over time, through reading, conversations with people in academia, family discussions, and moments of introspection, I’ve come to realise just how profound these beliefs are. At their heart lies a rich philosophy that governs life, relationships, and our connection to the universe. This is what many now call Tani philosophy.

I came across a fascinating TED talk by Himani Chaukar, from Maharashtra, where she shares her thought-provoking views on Donyi Polo. It is a must-listen for anyone interested in exploring these aspects of tribal beliefs. She shares her journey of living among the Apatani and Nyishi communities in and around Ziro Valley. What struck me — and her —was the complete absence of scriptures. Unlike many other faiths, Donyi-Polo’s essence is passed down orally, through chants, rituals, and storytelling. This orality isn’t a weakness; it’s a testament to the depth of faith the people have in their shared collective memory. Chaukar points out that Donyi-Polo isn’t just about the sun and the moon as celestial bodies. It represents something far more abstract — a formless, omnipotent, and omnipresent entity. There are no temples, and no images of god, because Tani tribes believe divinity exists in every creation. This is one way of understanding why there are no organised religious forms, scriptures, idols or temples in this faith because one doesn’t need to fix god in one place or thing to be revered and prayed. Chaukar also touches on how outsiders often misunderstand these beliefs, labelling them as mere nature worship or animism. For me, the USP of her talk was how she unearths the moral and ethical principles embedded in the Tani worldview. Concepts like balance, reciprocity, and respect for all living beings are not just abstract ideas; they’re woven into daily life. She also highlights how these principles are tied to ecological harmony — something the modern world desperately needs. The most powerful message in her talk was how ‘Tani philosophy’ doesn’t just guide individual behaviour; it’s a collective blueprint for living. Whether it’s rituals, festivals, or everyday interactions, everything reflects an interconnectedness that many other systems of thought aspire to but often fail to achieve. I think her TED talk is a good starting point to enter into this domain. It’s available on YouTube, and I recommend it to interested ones.

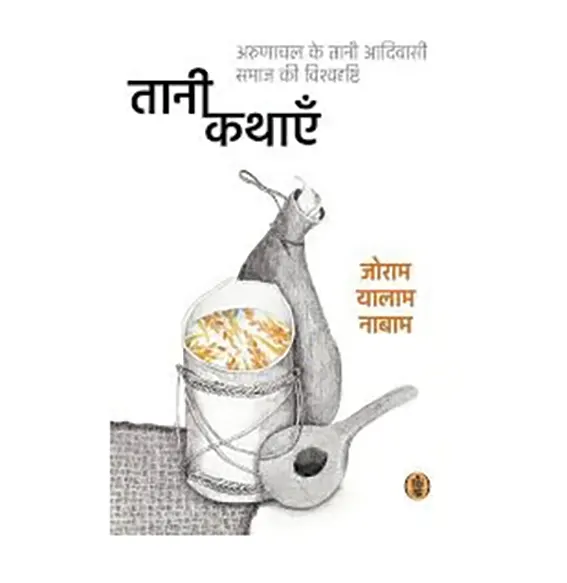

Shifting focus to Joram Yalam Nabam’s Tani Kathayein (2022) written in Hindi, I consider it a significant work — one of the first from Arunachal Pradesh, I must say – that delves into the core philosophy of the Tani people. The book is divided into two sections: Tani Darshan (Tani Philosophy) and Tani Kathayein (Tani Oral Stories), with the first section presenting an insightful exploration of the philosophy of Donyi Polo. In her introductory account, she narrates how she traversed different districts and met with people from all over the Tani belt. The stories and the philosophy in her book are thus constructed from an understanding of the different versions spread across all the Tani communities, from which the author has taken the liberty of choosing or constructing the versions she considered best. However, I wouldn’t consider this a limitation but rather a strength, especially in the face of challenges posed by the innumerable variations in oral stories, rituals, or practices. This is just one aspect of it; in the future, others may work on different versions or variations. However, it must be understood that at the core lies the same — Tani philosophy.

Nabam asks some pertinent questions in her book: How has Tani society remained disciplined and well-regulated for centuries without any organised religion, sacred texts, or notions of hell, heaven, sin, and virtue? How has the society, throughout the ages, sustained its love for its forefather, Abotani, who, though a heroic figure, is not venerated in the traditional sense? She believes that the answers to these questions lie in understanding the Tani way of life. Nabam explains the concept of Jimi-Jama, the primordial state of existence described as a state of “being yet not being.” Before the creation of time and light, there was extreme darkness, a womb-like silence named Jimi Ane or ‘Mother Jimi’. From this state emerged light — symbolised by the sun, moon, and stars — marking the birth of time and the beginning of existence. The earth, with the sun and moon, gave rise to water, air, and life, forming a harmonious bond akin to a marital relationship. This idea, where natural elements are perceived as companions rather than separate entities, lies at the heart of Tani philosophy. She further describes how the Tani people view nature as a living, breathing entity. Every tree, blade of grass, and even the dry logs of a house have life, ears to listen to, and voices to communicate. Donyi Polo is not a religion in the conventional sense; it is a way of life. The sun and the moon are seen as witnesses, as eyes of Jimi-Jama rather than figures demanding worship. Rituals and ceremonies are not bound by written scriptures or doctrines. Nyibus (priests) are not trained formally, they are not hereditary but they learn through oral traditions and a deep connection to their ancestors and the natural world.

The writer argues that tribalness, or Adivasiyat, is in itself a religion — a way of interpreting truth and existence that defies any fixed categorisations. The Tani worldview sees humanity and nature as interdependent. Life itself is considered a scripture, and living it with awareness and harmony is the ultimate prayer. The book also explores the social and moral fabric of the Tani people. Good and evil, auspicious and inauspicious occurrences are believed to arise from harmony or disharmony with nature. Every action is witnessed by the elements of nature, and reverence towards nature guides every action. Each person must be accountable for his decisions and actions in life. The Tani justice system, rooted in societal principles rather than written laws, ensures that balance is maintained. This interconnectedness is beautifully symbolised in the Tani language, where phrases like Donyi Kaado (“The sun is watching”) remind individuals of their responsibility to live in harmony with the natural world.

What I found particularly interesting in Tani Kathayein was Nabam’s exploration of Abotani, the forefather(s) of the Tani people. Unlike traditional heroes who inspire veneration, Abotani is a flawed, relatable figure, something like the Greek god Prometheus, who defied Zeus to help humanity and, despite his divinity, was also flawed. Tani’s story is not about divine perfection but about humanity’s struggles and triumphs. This lack of deification fosters a deep sense of connection rather than reverence, allowing the Tani people to relate to their ancestry on a profoundly human level. This, in turn, strengthens their bond with their own identity and community. The book also sheds light on the role of rituals in Tani society. Unlike organised religions that rely on sacred texts, Tani rituals are oral and intuitive, passed down through generations. Priests invoke the spirit of each entity, connecting the genealogy from Jimi-Jama to the present. This oral tradition ensures that the philosophy remains dynamic and adaptable, rooted in the lived experiences of the community.

In a world increasingly disconnected from nature, the Tani worldview serves as a poignant reminder of the beauty and wisdom inherent in indigenous philosophies. Just like Chaukar’s TED talk, and Nabam’s book, many other people and events have opened my eyes to the richness of Tani philosophy. It has also made me realise how important it is to bring these ideas into mainstream discourse — not just to preserve them but to learn from them. The world doesn’t need to look at Tani beliefs as ‘lesser’ or ‘different’. Instead, we need to recognise them for what they are: a profound way of understanding life, relationships, and the universe. It’s time to move beyond labels like ‘animism’, or ‘nature worship’ and start seeing the philosophy for its true worth. After all, isn’t every philosophy, at its core, an attempt to make sense of the world? The Tani tribes have been doing that for centuries, in their own way — one that is as valid, logical, and profound as any other. (Dr Doyir Ete is Assistant Professor, English Department, RGU. She is also a member of the APLS and Din Din Club.)