[ A.N.Mohammed ]

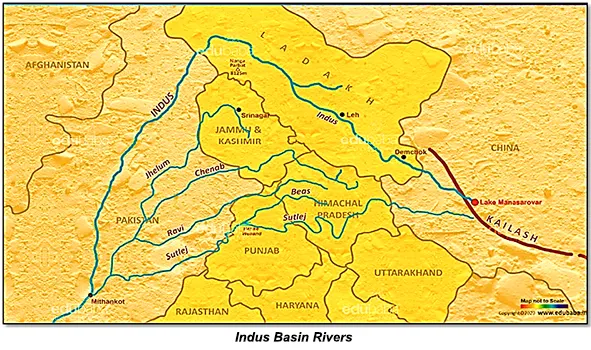

The Indus Water Treaty (IWT), signed on April 1, 1960, was a pivotal agreement between India and Pakistan, brokered by the World Bank to resolve water-sharing disputes of Indus River system after Partition in 1947. It allocated the eastern rivers-Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej-to India and granted Pakistan exclusive rights over the western rivers-Indus, Jhelum and Chenab, ensuring water resource distribution. Under this arrangement, India utilizes 20% of the system’s total water flow, while Pakistan receives 80%.

For more than six decades, the treaty endured wars and conflicts, standing as a rare example of diplomatic cooperation. However, following a terrorist attack in Pahalgam on April 22, 2025, India has suspended the agreement, halting water-sharing and potentially increasing its use of the western rivers, marking a significant shift in regional water management and geopolitical dynamics.

Sustainable Management of the Eastern Rivers

Abiding by the treaty, India utilises around 95% of its share of water in the eastern rivers through a network of dams, including the Bhakra on Sutlej, Ranjit Sagar on Ravi, and Pong and Pandoh on Beas primarily for irrigation in Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan and for hydropower generation. Shahpur Kandi dam on Ravi River in Pathankot, Punjab which has been completed recently, and the multipurpose project in Jammu & Kashmir on Ujh, a tributary of the Ravi will help India tap the remaining 5 percent of water that currently flows into Pakistan.

Before India’s partition in August 1947, several water infrastructure projects were developed on the Ravi and Beas River systems. The Madhopur Headworks, built in 1859, was among the earliest projects, diverting 1,821 MCM (Million Cubic Meter) of water through the Upper Bari Doab Canal to irrigate 3.35 lakh hectares across Gurdaspur, Amritsar, and Lahore.

Post-independence, India constructed the Bhakra Nangal Multipurpose Project on the Sutlej River between 1948 and 1963. By the time the Indus Water Treaty (IWT) was signed, 3,860 MCM from the Ravi and Beas systems was already in use for major irrigation schemes. To further harness the Sutlej, Beas and Ravi, several large projects were planned, including Naptha Jhakri, Harike Barrage, and Sutlej-Yamuna Link Canal on the Sutlej, Pong and Pandoh on the Beas, and Ranjit Sagar, Chamera-I, and Shahpur Kandi on the Ravi.

Initially, the unused river flow was designated for Jammu & Kashmir, Patiala and East Punjab States Union (PEPSU), Punjab, and Rajasthan. However, after PEPSU merged with Punjab, followed by Punjab’s bifurcation to create Haryana, disputes emerged over water allocation, leading to a tribunal under the Interstate River Water Disputes Act. A settlement reached on December 31, 1981, distributed 21,179 MCM of water annually: Punjab (5,205 MCM), Haryana (4,317 MCM), Rajasthan (10,608 MCM), Delhi Water Supply (247 MCM) and Jammu & Kashmir (802 MCM).

The Indira Gandhi Canal (originally, Rajasthan Canal), which is the longest canal in India (650 Km). It starts at the Harike Barrage, a few kilometres downstream of confluence of the Sutlej and Beas rivers in Punjab and ends in irrigation facilities in the Thar Desert in Rajasthan. Construction of the canal started in 1952 and completed in 2010. It is a gigantic canal project to carry 524 cubic meter per second water from the Harike Barrage in Punjab, to the Thar Desert, in Western Rajasthan. The canal network is spread in an area of about 60 km wide and 1,000 km long belt. It consists of feeder of 204 km, main canal of 450 km, distribution networks of 8000 km with several thousand km of lined water courses. It spreads over a gross command area of 25 lakh ha and provide irrigation to a culturable command area of 15.5 lakh ha.

The Sutlej-Yamuna Link (SYL) Canal was planned as a 214-km-long canal to distribute surplus Ravi-Beas waters between Punjab and Haryana. Haryana completed its portion of the canal, but Punjab halted construction after completing about 85% due to a long-standing dispute. The canal was expected to irrigate 4.46 lakh hectares in Haryana and 1.28 lakh hectares in Punjab, along with generating 50 MW of power. However, the project remains stalled due to legal and political disagreements between the two states.

The eastern rivers host several major hydropower projects spanning Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir and Punjab. On the Ravi River, key projects include the Chamera Hydroelectric Project (Stages I, II & III) with a combined capacity of 1,107 MW, the Baira Siul Hydroelectric Project (198 MW) and the Ranjit Sagar Dam (Thein Dam) (600 MW). Additionally, the Shahpurkandi Hydroelectric Project (206 MW) and the planned Ujh Hydroelectric Project (186 MW) further enhance power generation and water resource management. The Sutlej River, known for its hydropower potential, features major installations such as the Bhakra Dam (1,325 MW), Nathpa Jhakri Hydroelectric Project (1,500 MW), Rampur Hydroelectric Project (412 MW), and Karcham Wangtoo Hydroelectric Project (1,200 MW). The Baspa-II Hydroelectric Project (300 MW) utilizes a tributary of the Sutlej, while the Lubri Stage-I Hydroelectric Project (210 MW) is slated for commissioning in 2026. The Beas River plays a crucial role in inter-basin water transfers, with the Pandoh Dam (990 MW) diverting waters to the Sutlej, alongside the Pong Dam (396 MW) and the Beas-Sutlej Link Project. The Dehar Hydroelectric Project (990 MW) supports this linkage, while the Shanan Hydroelectric Project (110 MW) stands as one of India’s oldest hydroelectric facilities. Collectively, these projects enhance energy production, irrigation, and water management, reinforcing India’s commitment to sustainable hydropower development.

Management of the Western Rivers

Though India has constructed dams and run-of-the-river hydro projects on the Indus basin, they are not enough to harness the full potential of the water flowing in the Indus riverine system. India has several major hydropower projects on the Jhelum, Chenab, and Indus rivers, particularly in Jammu & Kashmir.

Some key projects include, on the Jhelum River, the Uri Hydroelectric Project (Stages I & II), with capacities of 480 MW and 240 MW, is a vital power source in Baramulla, Jammu & Kashmir, alongside the Kishanganga Hydroelectric Project (330 MW), which utilizes a tributary of the Jhelum. The Chenab River features significant infrastructure, including the Pakal Dul Hydroelectric Project (1,000 MW) in Kishtwar, the Ratle Hydroelectric Project (850 MW), currently stalled due to treaty disputes, and the Baglihar Hydroelectric Project (900 MW), which has faced geopolitical concerns related to water-sharing agreements. Additional developments on the Chenab include the Salal Hydroelectric Power Station (690 MW), the Kiru Hydroelectric Project (624 MW), and the planned Kwar Hydroelectric Project (540 MW). Notably, the Sawalkote Hydroelectric Project (1,856 MW) is among the largest proposed ventures, alongside the Dulhasti Hydroelectric Project (390 MW with 260 MW expansion), Kirthai-II Hydroelectric Project (930 MW), and Bursar Hydroelectric Project (800 MW), designed for water storage. On the Indus River, the Nimoo-Bazgo Hydroelectric Project (60 MW) in Ladakh stands as a critical high-altitude power station, strengthening energy generation in the region. Collectively, these projects shape India’s hydropower strategy, balancing energy production with water resource management amid evolving geopolitical challenges.

Pakistan has developed several multipurpose hydropower and irrigation projects to strengthen its water management and energy security. On the Indus River, the Tarbela Dam (4,888 MW) stands as one of the world’s largest earth-filled dams, while the upcoming Diamer-Bhasha Dam (4,500 MW) is poised to be a significant addition. The Dasu Hydropower Project (4,320 MW) is under construction, further expanding the region’s capacity. Smaller projects like the Patrind Hydropower Project (147 MW) contribute to localized energy needs through run-of-the-river mechanisms. Meanwhile, on the Jhelum River, Pakistan has established key infrastructure such as the Neelum-Jhelum Hydropower Project (969 MW) and the Mangla Dam (1,150 MW). Other major developments include the Karot Hydropower Project (720 MW), Azad Pattan Hydropower Project (700 MW), and Gulpur Hydropower Plant (102 MW), each playing a crucial role in optimizing Pakistan’s hydropower potential. Collectively, these projects support energy production, irrigation, and sustainable water resource management in Pakistan.

Treaty Under Pressure:

Despite enduring for over six decades, the Indus Water Treaty (IWT) has faced persistent challenges, particularly due to Pakistan’s objections to various Indian hydropower projects. The Salal project suffered from sedimentation issues due to design modifications. Disputes over the Kishanganga and Ratle projects led to international arbitration, delaying their implementation. Similarly, the Tulbul project, a navigation lock-cum-control structure at Wular Lake, was abandoned due to Pakistan’s opposition, despite its potential benefits for river transportation and water storage. However, the Baglihar project’s design was largely upheld by the World Bank, setting a precedent for future hydropower development in the region.

Implications of Treaty Suspension:

The suspension of the Indus Water Treaty and potential restrictions on water flow from the Indus River system will have severe consequences for Pakistan’s water security, agriculture, and hydropower generation. The Indus Basin considered as Pakistan’s lifeline has a mean annual flow of 176 BCM, of which 166.5 BCM (95%) received from India and utilized for almost 90% for irrigation purposes. Most of the flow in the Indus River (around 40-70%) is from glacier melt and snow off the Himalayas. The average precipitation in the basin is around 230 mm/year and most of the flow (about 85%) in the basin’s catchment occurs from the months of May to September. India now stops sharing hydrological data such as water flow information with Pakistan, which Pakistan relied heavily in management of its water resources, floods and droughts.

India’s water management landscape has undergone a significant shift, as it is no longer constrained by treaty restrictions on the western rivers-Indus, Jhelum and Chenab. This newfound flexibility allows for expanded hydropower development and enhanced water storage capabilities. The construction of large storage-based hydropower projects could temporarily halt downstream flow until reservoirs reach capacity, followed by sudden releases that may cause substantial surges in downstream levels. Additionally, large-scale river-linking initiatives aim to transfer 166.5 BCM of water from the western rivers to the eastern river systems would be supporting hydropower generation and irrigation across Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan and Gujarat. These developments carry profound implications for regional hydro-politics, potentially reshaping water allocation and interstate relations.

The evolving dynamics of water management have the potential to reshape South Asian geopolitics, intensifying discussions on shared resources and cross-border sustainability. The Indus and Sutlej rivers originate in Tibet, China, and flow into India and Pakistan, playing a crucial role in agriculture and hydroelectric power. The Indus begins near Mansarovar Lake and Mount Kailash, passing through Ladakh before entering Pakistan. The Sutlej merges with the Spiti River, moves through Himachal Pradesh and Punjab, and supports the Bhakra Dam before joining the Indus in Pakistan. While China has built hydroelectric projects near their sources, only a small portion, 10 to 20% of their water originates in Tibet, limiting the extent to which their flow can be controlled for geopolitical influence.

As reported, China is accelerating the construction of key dams in Pakistan as the country faces challenges in agriculture and industry following India’s suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty. One such project, the Mohmand Dam on the Swat River, is designed for power generation, flood control, irrigation, and water supply. It is expected to generate 800 MW of hydropower and provide 1.14 million cubic meters of drinking water daily to Peshawar, the largest city in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

As an upper riparian state, China plans to harness the waters of rivers that flow into India. China already announced construction of 60 GW mega-dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo River. Such a colossal project could severely disrupt downstream water availability, potentially triggering seasonal droughts and sudden floods in Indian’s northeastern states of Arunachal Pradesh and Assam. This, in turn, poses significant risks to agriculture, livelihoods, and ecological stability. To safeguard its interests and ensure regional water security, India must act decisively through strategic hydropower development, proactive diplomatic engagement and comprehensive water management policies. (The contributor is consultant, hydropower development in NE India. He can be reached at abunesar@gmail.com)