[ Dr Jajati K Pattnaik ]

The Kibithoo formula has immense potential to be a catalyst in generating trust and confidence between India and China. It could be vital to the Sino-Indian engagement, given its geo-economic and geo-strategic elements.

Geo-economic element

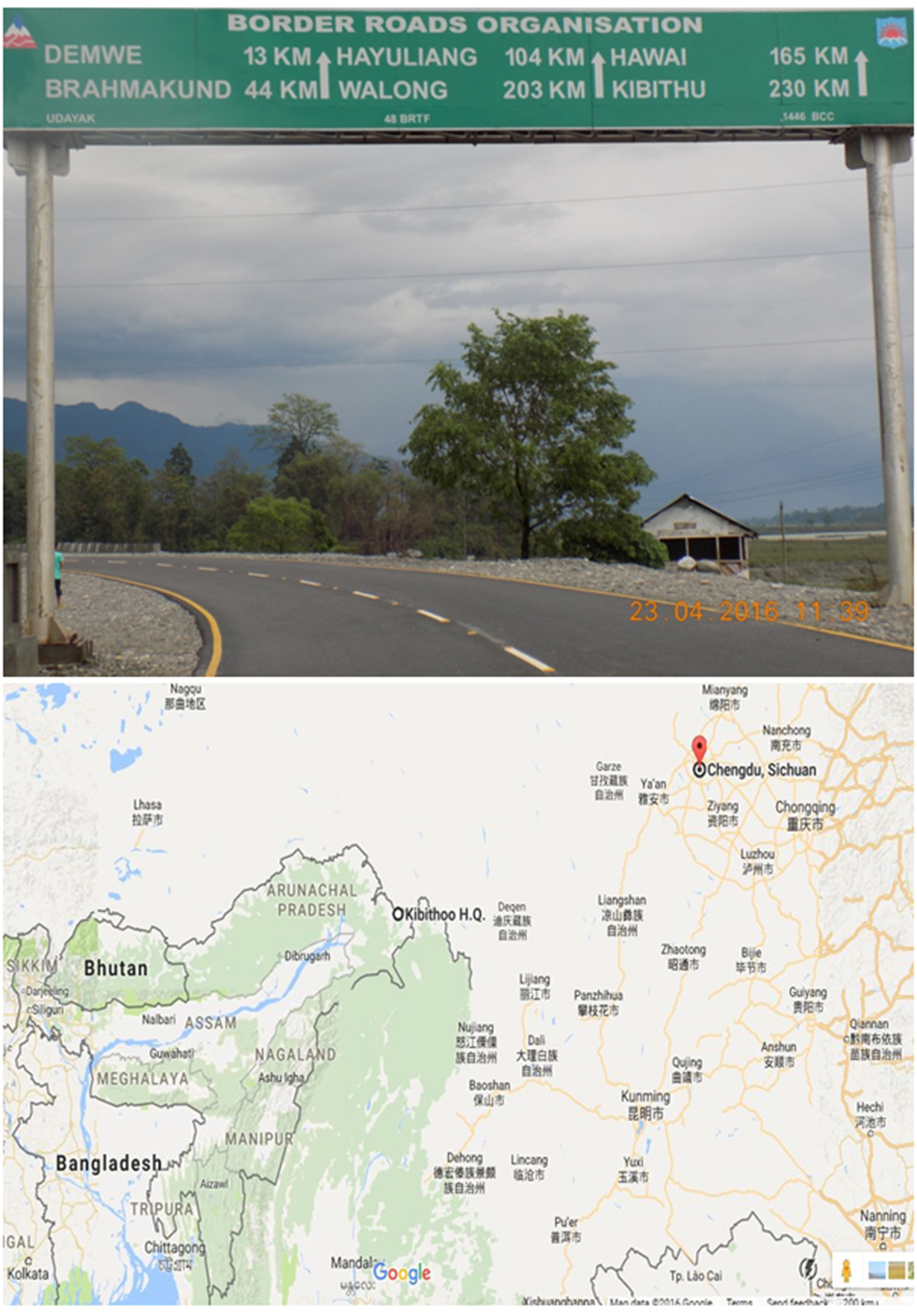

Kibithoo is situated in Anjaw district of Arunachal Pradesh, bordering China. It is 230 kms from Tezu, the district headquarters of Lohit. It was a natural passage between Tibet and India’s North East Frontier Tract during the British colonial period.

Kibithoo is important from the geo-economic perspective, and it is the most suitably located area in the entire Himalayan mountain range. It is situated at an altitude of 4,070 feet above sea level, compared to Nathula Pass, which stands at an altitude of 14,400 feet above sea level.

Even in Arunachal, the low elevated mountain range of Kibithoo enjoys geo-economic advantages over other mountain passes such as Bumla, Taksing, Mechuka, Monigong and Gelling.

Even in Arunachal, the low elevated mountain range of Kibithoo enjoys geo-economic advantages over other mountain passes such as Bumla, Taksing, Mechuka, Monigong and Gelling.

Kibithoo as a land port would be more beneficial in terms of land connectivity corridors, compared to the Stilwell road. On the other hand, if the Kibithoo project is taken up, it would provide shorter and faster access to the Indian industries to tap the southwestern and southeastern Chinese markets, and it would create adequate space for the emergence of industrial clusters, ie, Guwahati- Tezpur-Jorhat-Dibrugarh-Tinsukia Digboi-Margherita in Assam; Dimapur-Kohima-Mokokchung in Nagaland; and Itanagar-Ruksin-Pasighat-Roing-Tezu-Hawai in Arunachal.

As retired lieutenant general of the Army’s eastern command, John Mukherjee, through an electronic mediated response said to this writer, “Tezu-Hayuliang-Walong-Dichhu Pass-Rima is the shortest route to mainland China and offers tremendous potential to both Look and Act East for the entire region, provided the Indian government wishes to do so.”

Giving a comparative perspective, he observed that “the Stilwell road has only limited potential and, that too, only with Myanmar.

There is also the necessity to resolve the insurgency on both the Indian and Myanmar sides of the border, failing which the movement would not be feasible.”

Kibithoo as a land port would provide easy access to National Waterway II (NW II) route on the river Brahmaputra. It is pertinent to mention that the Brahmaputra river was declared a national waterway-II in 1988, covering a distance of 891 kilometres from Dhubri to Sadiya in Assam. The Inland Waterways Authority of India (IWAI) provides terminal services in key locations for loading and uploading of cargo at Dhubri, Jogighopa, Pandu, Silghat, Neamati and Dibrugarh. The IWAI is developing Pandu port in Guwahati as a multimodal transport corridor to cater the interests of the whole Northeast. In this context, NW II would prove to be highly beneficial in terms of cost efficiency for cargo movement as compared to the congested traffic of the highways.

Sadiya is only 345 kilometres from Kibithoo, and the cargo from Lower as well as Upper Assam can be transshipped through the Dhubri-Pandu-Sadiya inland waterways. Again, from Sadiya the goods can be transported through the Tezu-Hayuliang-Walong-Kibithoo land corridor on its way to Rima, Chengdu and Kunming in China. It is quite pertinent to mention here that India’s longest road bridge, Dhola-Sadiya, could be a game changer in India’s cross border trade vis-à-vis China. Equally, the country’s longest rail-cum-road bridge, Bogibeel, would also prove to be a catalyst for cross-border trade, reinforcing the pace of interstate connectivity between Upper Assam and Arunachal through the Trans-Arunachal Highways.

Geo-strategic element

Kibithoo as a land port would counter Chinese penetration into the region while reinforcing India’s strategic significance along the McMahon line. China has already built several infrastructure projects across the international boundary, including opening up a new highway link to Medog -‘Tibet’s Nyingchi prefecture’ – which is nearer to India’s land border in Arunachal.

Thus, India should vigorously move forward to construct the 2000-kilometre frontier highway along the international boundary from Mago-Thingbu (Tawang) to Vijaynagar (Changlang), covering upper hill areas of West Kameng, East Kameng, Upper Subansiri, West Siang, Upper Siang, Lower Dibang Valley and Anjaw districts for the development of its frontier territory and build multiple trade corridors prioritizing the most viable one – Kibithoo. The development of Kibithoo as a land port would give chance to both India and China to switch their priorities from security to trade or economic collaborations based on sustainable engagement paradigms. In this context, the Nathula model may be emulated in Arunachal to boost trade and commerce across political boundaries.

Notwithstanding its potentialities, the development of Kibithoo as a land port in Indo-China border trade is still in a conceptual stage, although it has many backers at the civil society level. No such proactive step has yet been initiated by the political machineries, possibly due to Chinese intransigence over the McMahon line. Hence, the need of the hour is to break the Sino-India deadlock over the boundary row and grab the opportunities through cross-border collaborations. That’s why proactive and sustained dialogues are to be pursued for economic engagement between India and China, going beyond the McMahon line.

While calculating the pros and cons, Kibithoo should not be treated as a mere land bridge; rather, the potentialities of Arunachal should be harnessed in order to expand the export basket of our country vis-à-vis China. Otherwise, Arunachal would be a dumping ground for Chinese products, which in turn would adversely affect India’s long-term economic interests. What is required at this stage is a joint Sino-Indian effort to transform this territorial boundary zone into economic opportunities for a win-win situation for all the stakeholders. Else, it would remain purely a wishful thinking. (The writer is Head, Political Science Department, Government Model Degree College, Roing, Lower Dibang Valley.)