[ Ranjit Barthakur & Joanna Dawson ]

The National Mission on Edible Oils – Oil Palm was introduced on 18 August by the cabinet, aiming to reduce overall national dependence on oil palm imports by increasing local cultivation. The mission specifically focuses on the Northeast, encouraging farmers to cultivate oil palm through Rs 11,000+ crores in support. This has ignited an animated debate about the prospects of oil palm, particularly for the ecology in the region.

Oil palm globally has a long history of ecological and social devastation in

Southeast Asian countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia. In West Africa, oil palm plantations were ground zero for the emergence of Ebola as fruit bats from nearby forests were brought into increasing contact with people. Previous attempts at rollouts in India have had limited buy-in, with farmers pointing to the long maturation period as a deterrent in an already financially and economically stressed profession.

The economic, social and ecological implications of oil palm in the Northeast

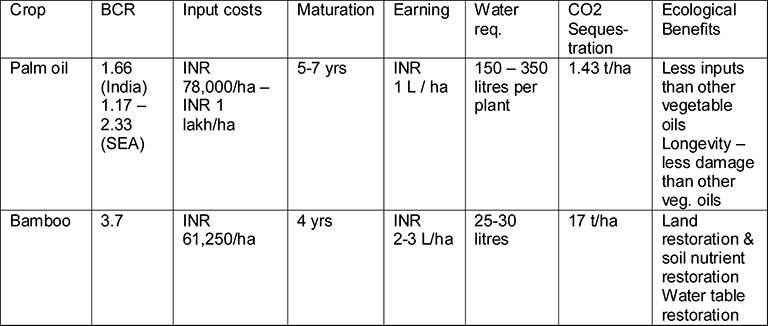

Compared to other endemic cash crops such as bamboo, oil palm has a much lower benefit-cost ratio, higher input costs and maturation period, and offers few ecological benefits. The table below compares the figures:

As a non-native species to this agroclimactic zone, oil palm requires far more inputs to thrive compared to endemic species: from water to pesticides, driving up overheads and risks for farmers. Over 12.75 percent of the Northeast’s land is desertified, rising to as high as 40 percent in states like Nagaland. Chemical intensive cultivation will only accelerate this, as will its cultivation on the slope terrain of the Northeast. Climate projections by the ICIMOD show that the Northeast will lose more water than it receives through rainfall over the next decade, while groundwater continues to deplete (each state loses an estimated 5000 m3 annually). The Northeast’s high rain-fed agriculture dependence will lead to increased water stress and climate vulnerability: an oil palm tree requires 150-350 litres of water daily. Meanwhile, processing oil palm generates 2.5 t of effluent for every tonne processed and will pollute already at-risk water systems.

Farmers across India report incurring losses of up to Rs 7 lakhs while waiting for oil palm to mature. In a region of 80 percent marginal farmers, such losses will further increase income insecurity, indebtedness and entrench marginalization. The subsidy push risks food crops being replaced with oil palm: the Northeast is already facing a nutritional crisis, with childhood stunting on the rise in five states as per the NFHS-5. Early attempts under Mizoram’s land use policy disenfranchised women, as collective jhum lands were privatized and control was transferred to men, leading to loss of livelihoods and decision-making.

Ecologically, oil palm deforestation will compound climate vulnerability and lead to increased human-wildlife conflicts with species such as Asian elephants, leopards and tigers, while accelerating the economic vulnerability of forest-fringe communities. It will risk our global net zero goals and India’s commitments to create a 3 GtCO2e carbon sink under the Paris Agreement. Oil palm in SEA has net emissions of 174t/ha owing to clearance and cultivation practices. In both Malaysia and West Africa, these plantations have become disease vectors: Ebola in West Africa, malaria and dengue through increase mosquito populations in Malaysia. New pests introduced through these non-native species will likely create further disease risks.

A climate-smart, future-oriented approach

The next 5-15 years are make or break for the NER’s climate longevity. Long-term earning and jobs through sustainable agriculture must take centre stage to build the resilience of local markets through bamboo, rattan and sustainable timber. A full boost to the NER economy for agroforestry and forest rewilding will generate Rs 84,000 crores from year three onwards and reach Rs 450,544 crores at a 30 year maturation period, creating jobs for two million households. Endemic species such as the lucrative bamboo must be encouraged and supported by science-driven, climate-informed policies. Policies need to be streamlined to support commercial growth on farmlands, as well as to invest in agro-climactic studies of species for informed recommendations and science-driven support systems for farmers.

Sustainable, organic oil palm agroforestry experiments in Brazil led to yields of 180 kg per plant, against 139 kg per plant in chemical-fed monocultures. Combined with staple food crops and other endemic cash crops, Brazilian farmers minimized financial and food security risks while maximizing income gains. The model offers a possible template for sustainable rollout in the NER. Oil palm alternatives that are endemic to the country such as coconut oil, sunflower and black seed should be encouraged and incentivized, especially as consumers move away from palm oil because of cholesterol concerns.

Strengthening rural communities will be the key to unlocking our natural capital for a resilient climate and ecological future. The Northeast is easily the richest geography in India, when we account for the natural capital held in its rich, diverse forests and landscapes. Our ecology is our economy. For our rural communities, we must work to build a naturenomics™future of interdependence and thriving ecological civilizations. (The contributors are with the Balipara Foundation, Assam.)