Tribal Bookworms

[Dr Bompi Riba]

One of my most recent readings that fascinated me a lot was a folktale from Tawang, titled ‘Zombie’, authored by Tumbom Riba. It is a term that has its origin in Haitian folklore, in which the dead body reanimates through various methods, most commonly magical practices like voodoos. In popular culture, zombies often appear in science fictions where magic is seldom involved. It is through scientific methods like radiations, parasites and scientific accidents that trigger a zombie apocalypse. This term entered the English lexicon after the British poet Robert Southey used it in 1819. Apart from the traditional version of ‘zombie’ as found in Haitian folklore, in the latter half of the twentieth century there were lots of movies that interpreted ‘zombie’ as an undead person that attacks and eats the flesh of living people.

While our familiarisation with such phenomena in sci-fi movies have contributed towards naturalising the term ‘zombie’ in our discourse, we remain unaware of such characters thriving in our folktales. That is also the reason why the unusual title ‘Zombie’ among the list of folktales in the collection Kaatam: Arunachal Pradesh ki Janjatiyo ki Lok-Kathaye (2020) triggered my curiosity to serve as a catalyst to run through the pages in haste. What intrigued me was the translator’s choice of the word ‘zombie’ over the traditional ‘rolang’, which is a combination of two syllables, viz, ‘ro’ meaning ‘corpse’ and ‘lang’, ‘to rise’. In other words, ‘rolang’ means ‘a risen corpse’. Foucault had rightly pointed out that the most effective tool for excluding and controlling types of knowledge and behaviour is discourse, which articulates preferred social ideologies. By excluding the word ‘rolang’, the translator has undermined the legitimacy of this word which represents a belief system that had a remarkable influence on the lifestyle of the people from Mon region, which is evident in places like Lish village in West Kameng district, where traditional houses used to have short doors to prevent rolangs from entering. It is worth noting how the architects of these houses were influenced by the folktale which had infused the belief among the locals that since rolangs were risen corpses, they could not bend. Interestingly, in the folktale, the rolang does not rise because of any voodoo or scientific accident. It simply rises as if it is the most natural thing to do. This is in fact a representation of the community’s belief in supernatural phenomena. However, the story also serves the purpose of conveying the message of moving on in life despite adversities.

Often the problem with translation is that we tend to think of it simply as an act that incorporates translating a language, ie, the meaning of it. What we overlook is how in the process we are also translating power. For instance, the term ‘zombie’ and its associated idea are so established that it has become a fixed idea. The fact that the translator has also chosen this word over the traditional ‘rolang’ has furthered its social hierarchy over the latter. So, the question of the ethics of translation surfaces as to ‘why’ and ‘for whom’ this folktale was translated. There might have been a compromise with this word, which also suggests the notion of interculturality. As a consequence of which the hawk’s eye of the critic zooms in to examine the translator’s ethics in translating as they are the byproduct of one’s conscience and reasoning. Therefore, it becomes imperative to deduce that the target readership of the collection, Kaatam: Arunachal Pradesh ki Janjatiyo ki Lok-Kathaye is the mainstream readers.

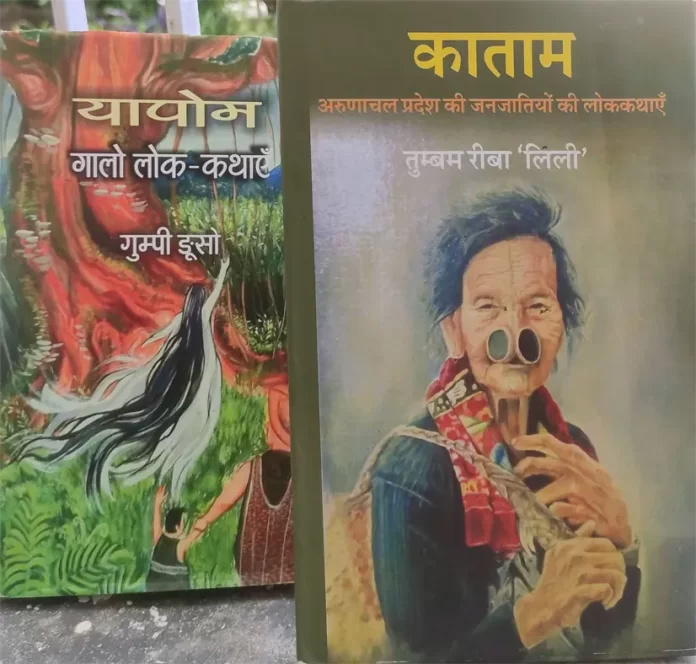

This assumption is confirmed when one looks at the cover of the book, which consists the image of an Apatani woman with nose-plugs and a tattooed face. This is definitely a marketing strategy as the collection does not consist of a single Apatani folktale. This observation seems logical in the context of selling the book by exoticizing the indigenous subject. Nevertheless, the translator deserves praise for bringing out this folktale for the reading public. The collection Kaatam: Arunachal Pradesh ki Janjatiyo ki Lok-Kathaye consists of 14 Galo folktales, two Nyishi folktales, two Adi folktales, one Tagin-Nyishi folktale and one folktale from Tawang. Among the 20 folktales, 19 belong exclusively to the Tani belt. The translator must be appreciated for the effort she has made in collecting the folktales and making them available for the reading public. While she seems to be outstanding in her narration of folktales from the Tani belt, one can notice the initial awe in the narrative regarding the strange and unnatural situation in a place called Dudunghar, where in the remote past the natives would even worship ‘evil spirits’ and ‘zombies’ or ‘rolangs’.

Another collection of folktales worth mentioning is Gumpi Nguso’s Yapom: Galo Lok-Kathaye (2021). The picture in the cover of this book conveys a message that reflects an aspect of the Galo worldview. It consists a woman who is apparently supernatural as she is seen floating in the air towards a huge tree. As the title of the book suggests, one can assume that the woman in question is a yapom and according to the Galo beliefs, yapoms dwell in huge trees. In the picture, there is also a man holding the hand of his son. Both of them are in traditional attire. Their bodies seem relaxed and not tensed at all. What is interesting about this picture is that at first glance it is left to the imagination of the beholder to reckon whatever they want to believe as all the characters are seen from behind. But after reading the story, the picture is viewed from a perspective inherent in the folktale. It does not at all sensationalise the yapom, which, according to the folktale, is a spirit that dwells in dense jungle. Though a faint similarity is noticed in the characteristics between a yapom and a banshee found in Irish folklore, the author’s choice of the indigenous word is commendable. She tactfully retells the story of Ato Japo and his yapom-wife, Pomre Yaza without being offensive and too anthropological. She also introduces the readers to traditional words such as silak for bamboo tubes for carrying water, biro (mythical water creature), yirne (creator), etc, in the narration. The story underscores the belief of the Galos in yapom, but what is special about this narrative is the way the author has given a considerate portrayal of Pomre Yaza, who gives up her world and power for Ato Japo and their son Polo. In this way she projects the yapom as an archetype of the sacrificial woman that is often found in folklores.

Translation is an important business that is to be taken seriously. Since the traditional beliefs and values of a community have their roots in their folktales, the translators must make themselves well-acquainted with their history, culture and social structures. In other words, translation does not involve simply converting words from one language to the other. One has to be sensitive and respectful towards the culture that is being represented in the folktales. Therefore, in order to maintain their authenticity, it becomes indispensable for the translators to understand the cultural context from which these stories emerge. Otherwise, it is natural for women/men to be flabbergasted by stories like that of the ‘zombie’/rolang or the ‘yapom’. (Dr Bompi Riba is Assistant Professor, English Department, Rajiv Gandhi University, Rono Hills. She is also a member of the Arunachal Pradesh Literary Society and Din-Din Club)