On Arunachal’s poetic expressions

[ Dr Doyir Ete Taipodia ]

A modern Arunachal needs a literary body of its own; a literary tradition that embodies the literary spirit of Arunachal, reflecting its essence and tribal ethos. Poetry, the oldest literary genre, is the closest, most natural, and first medium for any soul who wants to sing, express, and share thoughts and emotions most lyrically. When the famous British poet William Wordsworth described poetry as “the overflow of powerful emotions,” he truly captured the power behind emotions expressed in words. Similarly, American poet Rita Dove said, “Poetry is language at its most distilled and most powerful,” highlighting language’s barest, elemental, and purest form in poetry. One must read its literature to truly understand a society and its people. Here at Tribalbookworms, we have the pleasure of introducing the creative works of authors and offering readers a taste of the rich stories and poems from our state.

One such author is Yumlam Tana, a poet and novelist,who belongs to the Nyishi tribe. Donning multiple roles — an author, a modern man, a tribal man, a Nyishi, and an Arunachali — he has carved a niche for himself among recognised writers from the state. This article focuses on his poetry, which is both rich and expansive, touching upon a wide array of themes. His work is crucial to understanding the evolution of English poetry in Arunachal.

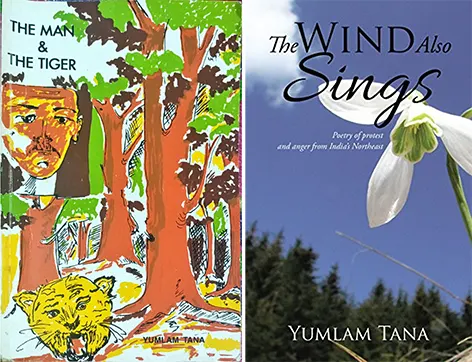

Tana is the author of two volumes of poetry, The Man and the Tiger (1999) and The Wind also Sings (2015). His poems appeared in the Anthology of Contemporary Poetry from North East India (2003), The Borderlands of Asia: Culture, Place, Poetry(2017), and the Penguin Book of New Writings from India, Vol 4 (2008). His novel, The Place Where the River Meets(2020), is a powerful narration of love and revenge, which will be taken up in a future article. However, it is a must-read for its depiction of the vicious cycle of revenge, which is not uncommon in our society.

Tana’s poetry is a commentary on the culture and the social and political movements of our state. His concerns about tribal identity, issues of racism, the education system, corruption, and the plight of the youth resonate with today’s young generation. Tana also draws from the rich folk culture of various tribes, particularly his Nyishi tribe. Those interested in ethnopoetic depictions of folklore and stories will find satisfaction in how these elements are incorporated into his poetry.

The Man and the Tiger is his first book of poetry, published by Writers Forum, Ranchi. The poems in the collection interrogate the poet’s own reality and identity as a modern tribal man. Writing for him is an act of assertion and finding one’s identity. Tana uses poetry as a medium, a tool, a voice, an expression, and a source of aesthetic pleasure. Poetry to him is, in his own words, “like mind making love.”

The poems are diverse, offering insights into modern sensibilities and the sensibilities of folk tradition. They provide a glimpse into the poet’s concerns and influences, highlighting his indebtedness to the folk tradition of his tribal history.

His first book of poetry, titled The Man and the Tiger, includes the titular poem, which is my personal favourite. The poem is based on a myth that traces the genealogy of man and tiger back to a time when they were brothers from the same parents. The man-tiger relationship is sacred and spiritual in many tribes of Arunachal, and there are numerous oral stories suggesting this. This poem also brings to mind the Romantic poet William Blake’s The Tyger, particularly in its celebration of the wonder and awe of the tiger. While Blake’s tiger is framed within a theological context, Tana’s tiger is rooted in the popular folk stories of the Nyishi tribe.

It is important to understand the inner beliefs of such indigenous stories, especially in modern times when human-nature dynamics are becoming increasingly complex and nature is almost on the brink of tipping over. Tribal cosmology and worldview were always closely interlinked with nature, promoting sustainability for all. Perhaps today’s modern world could learn a lesson or two from these beliefs. The mythology illustrates the close relationship between humans and nature, which is the source of all cultural stories.

Another poem, The Kurta and the Pyjama, in the book encapsulates the experience of a modern man at a crossroads, struggling between tradition and modernity. It explores the poet’s psyche as a Nyishi-tribal-Indian, bewildered by the hybridisation of his identity. This poem examines the identity of an Indianised Nyishi man who thinks in Nyishi, writes in English, and wears the kurta and pyjama instead of his traditional attire the ‘pomo’. These identifications are even more complex because, at the core, there is a search for identity as a Nyishi tribal man.

The book also reveals Tana’s admiration for figures who influenced his writing and worldview. The poems Ted Hughes and Lou Majaw are interesting dedicatory poems. However, the first book is more reflective and introspective, containing flashes that promise riches in future works, as achieved in his second book of poems, The Wind Also Sings, and his novel The Place Where the River Meets.

Over the years, his poetry has evolved, becoming more intense and raising significant questions about the current state of society. His second volume of poetry shows a more mature approach, perhaps influenced by his experience as a government officer, which provides opportunities to interact with the common folks of the state. This evolution is reflected in the subtitle of the second volume, Poetry of Protest and Anger from India’s North East.

This book contains another of my favourites, the poem, Journey to Tibet, which is based on a Nyishi folktale about two brothers and their sister and their journey to Nyime Nokul (Tibet) from Kuradadi. The sister, who insisted on joining her brothers for the journey, is warned to maintain the taboos toward the forests and their spirits. However, in her excitement, she throws all caution to the wind. Ultimately, she is engulfed by wild vines and turns to stone. The poem is rich in sensory details, as if we are actually witnessing the event and hearing the sad lamentations of the brothers and the sister.

Another poem, Yai, is a moving depiction of the loss of a mother and the pining one feels after her passing. In the poem A Tribal Man Speaks, Tana points to the simplicity of tribal languages, which, though lacking the ‘sophistry’ of evolved languages, do not lack in emotions and expressions. In another poem, On Leaving the Village, he presents an ironic image of Arunachal, the ILP, and the introduction of education in the state. In the poem I Will Tell You Why We Are Angry, he presents the loss of the old ways of living, of innocence, honesty, respect for elders that have passed away from current generations. In the poem Who are we, he questions tribal identity and its meaning in modern day. The poems are imbued with a note of sarcasm and bitterness, reflecting his frustrations.

In his book The Wind Also Sings, Tana raises critical questions that touch upon the clash of cultures, racism, foreign gods, tribal identity, and the concerns of the youth in blazing words. He also touches upon the problem of intolerance and bigotry toward northeasterners outside of the region in his poetry. He uses poetry to vent his anger and frustration at the intolerance he sees around him.

Yumlam Tana represents the contemporary indigenous poet’s poetics concerning the socio-political state, the search for identity, the anxieties of contemporary times, and the need to articulate these. For him, poetry is the medium to achieve these. In his words, “Words will rise, like a mist, to sparkle like lights in water.” I hope that readers will pick up a book of poetry today and feel its power to touch hearts, spark joy, provoke deep thoughts, ignite curiosity, and create lasting memories. (The reviewer is Assistant Professor, English Department, RGU, and member of the APLS and Din Din Club.)