Tribal Bookworms

[ Dr Doyir Ete Taipodia ]

Recently, I had the good fortune to visit the Research Institute of World’s Ancient Traditions, Cultures and Heritage (RIWATCH) in the beautiful Khinjili village near Roing. I was quite amazed by the research work being done there and the involvement with the elders of the community. Equally impressive was the RIWATCH museum, with artefacts from across the world. What particularly stood out was how well the Idu Mishmi culture was documented and showcased, especially their shamanistic tradition. The Idu Mishmi have been at the forefront of preserving their shamanic tradition. In fact, the first shamanic centre was established in Mipi Pene in Roing in 2018.

The word ‘saman’, taken from the Tungus, an indigenous group in Siberia, Russia, means ‘to know in an ecstatic manner’ (Buzekova, 2010). In tribal societies, the shaman fulfils a multifunctional role: he is a healer, storyteller, genealogist, ritualist, and more. He is also a guide, believed to escort the soul to the land of ancestors after death. The shaman is a figure that holds a society together. The shaman is an institution in himself; he is a cultural figure around which a tribal community naturally thrives. In Arunachal, each shamanic society has its own term for this figure. While ‘shaman’ is the closest word we have, it often falls short of fully capturing its true essence. However, the central role of shamans in society is gradually shifting as communities adapt to modern, individual-driven lifestyles while navigatingso many other external influences.

When in 1882 Friedrich Nietzsche proclaimed, “God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him,” he was using a metaphor to describe the existential crisis of Europe during that period. The rise of science and modernity had gradually eroded traditional and religious beliefs and Nietzsche mourned the decline of Christianity due to it. In a similar vein, I can’t help but feel a connection to this sense of loss, especially observing how today’s society is gradually abandoning and distancing itself from shamanistic traditions in everyday life.

Today, many tribal faiths have been replaced by external religions like Christianity, Hinduism, and Islam. This shift has often led to the loss of tribal beliefs and practices. On the other hand, society has adapted to many changes influenced by new religious teachings.

Consider the role of alcohol in tribal societies. Many have chosen to give up alcohol due to the teachings of the church, which is undeniably a positive change. However, in some cases, alcohol has been replaced with fizzy drinks like Pepsi. It’s become so prevalent that people of all ages consume it like water. An article in The New Indian Express, titled ‘Not liquor, it’s thirst for soft drinks that gets Arunachal locals queued up’ (published on 17 May, 2020), highlights this craze for soft drinks. This phenomenon is no longer just about religious influence; it has evolved into a culture of its own — the ‘Pepsi culture’.However, this shift has raised serious health concerns, as discussed in The Arunachal Timesarticle, ‘Why this cola? Worry, ji’ (23 October, 2020). With the second Pepsi plant scheduled to open in Arunachal, as announced by the chief minister on 20 January, 2020, a future rise in serious health issues seems likely.

The influence of other religions like Hinduism is also seen in the changes in indigenous religious rituals, where elements, like burning incense, ringing bells, idolatry or chanting, are now being incorporated. This blending of traditions has become a part of ritualistic expression in many communities today,creating a neo-syncretic form of religious practice,very different from the traditional ones. Traditionally, a shaman is not hereditary; he receives a call from the spirits – he is chosen. He is endowed with special abilities. However, today, shamans are selected and trained. There are efforts to institutionalise shamans and shamanistic traditions. This is a poignant reminder of the deep cultural shifts and the impact these changes have on the heart of tribal traditions.

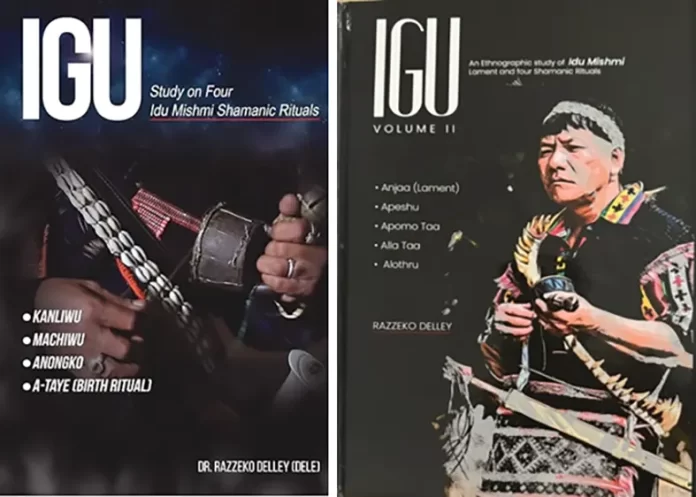

This brings me to a beautifully crafted book on shamanism by Razzeko Delley. His books Igu: Study on Four Idu Mishmi Shamanic Rituals (2021) and Igu: An Ethnographic Study of Idu Mishmi Lament and Four Shamanic Rituals (2023), with their attractive covers, almost invite us to dive into the ancient yet intriguing shamanic world of the Idu Mishmi. Delley’s book offers two significant benefits for general readers and academicians: it serves as a primary source for studying the igu (shaman) of the Idu Mishmi and ensures that this tradition is documented and preserved for posterity. These books detail the shamanic invocations of different rituals first in the Idu Mishmi language, followed by an English translation. Different rituals require igus with abilities specific to that ritual. These rituals address all aspects of human life — births, deaths, sickness, protection, house blessings, and more.

A reading of these texts provides insight into the Idu Mishmi cosmos, their beliefs and practices, which encompasses the human world, the wild, the spiritual world, and the netherworld. The supreme deity, known as Innyi Mashelo Zinu, is central to their beliefs, but there are countless other spiritual guardians and entities connected to almost every aspect of human life. Most spiritual guardians are personifications of nature, highlighting nature’s totemic significance within society.

Furthermore, detailed locations are embedded within the incantations, offering glimpses into significant places that have been crucial to the ancestors and continue to be revered both in the spiritual imagination and reality. For example, Mithunga, the spiritual place of mithuns; Adge, the ranges for hunts; Dondo, the spiritual place of pigs; Rock Athu,associated with the spiritual shaman Sineru and a stony cliff in the Talo (Dibang) river valley near the LoC on the Indo-China border, which is the sacred site the supernatural guardian Builiya.

In the Idu Mishmi cosmos, the tale of the origin of death provides insight into how death came to be and how the rituals of Anjjaa – the Idu Mishmi lament, began. The ritualistic animals and birds used, and their symbolic significance, also convey a wealth of knowledge about the tribe’s rich data on birds, animals, and plants. These books delve into fascinating stories from primordial times, exploring the tribe’s cosmology and the origins of water, grains, agriculture, and farming.

I’ve always been fascinated by the attire of shamans. In Idu Mishmi, this special outfit is called the amrala. The books beautifully explain the symbolism behind the different objects on the Amrala — the cymbals, the dao, tiger teeth, bird feathers, yak hair, and cowrie shells, each carrying significance. The ritualistic use of feathers, for instance, is particularly intriguing. During the Arebi ritual, the igu places a feather from the Aeto-abi (the sacrificial rooster) over a new mother. The author explains how this feather serves as a spiritual shield, protecting the mother and embodying healing powers, acting as a defense against evil. The author also discusses the priest’s use of archaic language, not just as tradition but as a necessity since the dead are believed to understand only the ancient shamanistic tongue. Laments, therefore, are more than expressions of grief — they make the dead hear you. This explains why, in shamanistic societies, funerals and laments are so elaborate, with shamans playing a crucial role.

I must confess that these books have also deepened my understanding of my culture and traditions. However, Delley laments the gradual decline of shamanistic tradition, which, in his view, leaves the Idu Mishmi society vulnerable to external influences. He believes that this is largely due to the absence of any codified, institutionalised, and documented record of their shamanistic practices and traditional faiths. This urgency gives his work more relevance today.

Documenting shamanism is not only challenging but also time-consuming. Translators are needed to decipher the archaic language. The researcher must follow shamans on their calls, and patiently interview them, especially considering their digressive narrative style, which uses roundabout tales to make a point and wait for occasions when shamans are called for their services. Scholars like Delley provide authentic and detailed primary sources that can bridge gaps, offering valuable resources for researchers engaged in time-bound academic pursuits. Also, like Razzeko Delley, upcoming scholars and members from other communities can draw inspiration from their society and culture, collect rich data and document them for the benefit of both researchers and their own communities. (Dr Taipodia is Assistant Professor, English department, RGU. She is also a member of the APLS and Din Din Club.)