TribalBookworms

[ Dr Bompi Riba ]

A fortnight ago, the court of the special judge (POCSO), west session division, Yupia, delivered a landmark judgement by passing the death sentence to the paedophile Yumken Bagra for his monstrous sodomy that physically, emotionally and mentally scarred the lives of many young children between the ages of 6 and 15. Along with him, Marbom Ngomdir, the Hindi teacher, and Singtun Yorpen, the headmaster, were each sentenced to 20 years in prison for abetting the abuse. While the verdict of the court brought a general satisfaction among the public, most of us were also shaken to the core when details of the abuse and the assault surfaced in the news. We can only imagine the kind of trauma these children had gone through in the hostel, which should have been a substitute for home but was more of a psychopathic criminal’s dungeon for them. My heart goes out to them because a person’s experience of place and home is mostly moulded by his/her childhood memories alongside his/her current experiences and the dream for a secured future. These emotions are inherently spatial and also contextual in nature. It is really disheartening to think that these children might still continue to associate their school lives with that hostel and the psychopath. I hope that they will overcome this nightmare. Even as I type this article today, I leave my prayer for them and their future.

Generally, home is considered to be a place of security, shelter and nourishment where one is free to feel at ease with oneself, without being bothered of surveilled or assaulted, but it is worth contemplating on how ironical and at the same time appalling and tragic that it is in their homes that women and children are the most vulnerable to violence and sexual assaults from their family members or relatives. In the Shi-Yomi case, the parents of the victims trusted the school authority, who failed them miserably and unfortunately, the caretaker became the predator of the children. It was easy for him to silence them by threatening them of dire consequences, mainly because they were young and innocent. However, when it comes to adult women, ironically, they can perceive danger from strangers in public places easily, but when it comes to violence at the hands of their own husbands, then they seem lost and do not have the same clarity in perceiving the lurking danger from a stranger. Usually, the violence committed by strangers is judged automatically as crime but when the violence is committed within the private and supposedly safe spaces of home by a known person such as the husband or the father, such act is considered to be normal and is not interfered by outsiders. This is something to be pondered upon, as the humanist geographer Nigel Thrift has also claimed that somehow all the ways of thinking about space and place are related to how power is constituted.

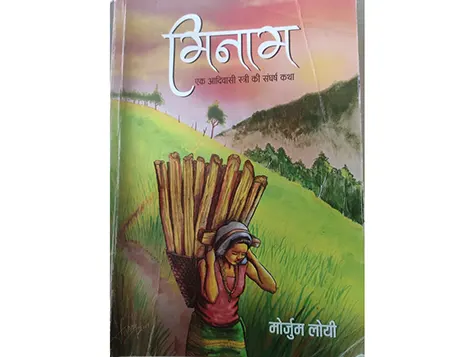

Interestingly, home has its own spatial practices, ie, the rules and regulations that restrict one’s behaviour within that space. It can be spatially demarcated into separate rooms to serve as bedrooms, living room, kitchen, dining room, bathroom and the verandah. Within the disposition of these rooms, the occupants are expected to execute spatially appropriate behaviours which, through the process of repetitive performance, become recognised as normal and natural. Home is not free from politics. It is influenced by the ideologies of various structures such as patriarchy, heterosexuality, capitalism and also racism. It influences as well as gets influenced by the social relations that are practiced both inside and outside the home. Morjum Loyi’s Minam: Ek Adivasi Stree ki Sangharsh Katha exhibits the female characters’ nostalgic longing as well as resistance to the home that encompasses the long-established traditional customs and beliefs of their community. Through this novel, the narrative of which comes across as anthropological at many instances, the author delineates on the configuration of a traditional Galo house to describe how it has its own unique spatial practices. To illustrate she refers to the hierarchical nature of its four corners, which are designated for specific purposes. For instance, ‘nyode’ is an area in the house earmarked for the use of elderly people such as grandparents; ‘bago’ is the space reserved for the activities of the male members of the house; ‘udu’ is the space allotted for young girls, and ‘nyosi’ is the space for the women in the house who are given the responsibility of running the hearth in the kitchen.

Further, the house also consists of two flights of stairs, one for the use of males and the other for females. A young girl who is still not an adolescent can use the males’ stairs. However, the traditional belief among the Galo tribe is that misfortune will fall upon a man if a menstruating female uses the males’ stairs or ‘bago’ or touches his things. She can be held responsible for man’s failure not just in hunting but also for his failure to make valid arguments in the ‘keba’ (or the local governing body). This accounts for the ambivalent nature of ‘home’ in the context of the Galo community. However, it is pertinent to locate the spatio-temporal specificity of the community’s behaviour as highlighted by the narrator in the novel. Considering the fact that the narrator does not provide the exact time period of the events in the narration and that she mentions that it was the time when Itanagar, the capital of Arunachal Pradesh, had only one college where the protagonist, Yami was a student. It can be assumed that the college in question is Dera Natung Government College, which was established in the year 1979.

Therefore, the events in the novel that narrate the ordeal of Yami in the village can be situated between the 1980s and the 1990s. So, the problems that are highlighted in the novel are characteristic of that time. The ill effects of the practices, such as, ‘nepenyida’ (‘marriage in wombs’ conducted between foetuses in the wombs of their mothers) and ‘lepalingnam’ (‘lepa’ meaning a wooden trap and ‘lingnam’ meaning ‘to put’ or a tradition in which the women were forcefully locked up inside a room with their hands tied and legs entrapped in a wooden trap until they surrendered to the men who had expressed their desire to marry them) are some of the important examples. But it is also to be noted that while such heinous customs are no longer in practice, domestic violence still persists in many houses, irrespective of the tribes of the state. According to the narrator, back in those days when ‘lepalingnam’ was considered a legitimized custom, in some cases, women were also forcefully raped and kept behind locked doors until they got pregnant. In the novel, while the protagonist Yami was a victim of ‘lepalingnam’, Minam’s mother was a victim of ‘nepenyida’. And in the case of Minam, she was a victim of domestic violence. She was subjected to marital rape and all kinds of abuses. When she could no longer bear the mental, physical and emotional torture from her husband, she separated from him. However, in her diary she wrote that as a divorcee, the society often made her feel like a woman who had fallen out of grace. In due course of time, she fell in love with a man from Bihar and got married to him. However, her marriage with a non-tribal man with whom she had two daughters often raised eyebrows among the locals, despite her being at peace and more compatible with him.

This episode in the novel can also be related to the burning offspring case in our state. It is noticeable that despite our long history of living amicably with the non-tribals, we have shown aversion to intermarriages with them primarily because of two reasons. Under the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation Act, 1873, Arunachal Pradesh falls under protected area and according to that Act, non-tribals, ie, people who are not native to the land, cannot “acquire any interest in land” (Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation Act, 1873) here. Originally, this Act was regulated concerning the safety of the British subjects trespassing into the prohibited NEFA (North East Frontier Agency). But after the independence of India in 1947, this particular Act turned out to be a boon in disguise for NEFA, which became a state in 1987. In consequence to the Act, the non-natives of Arunachal, who originate from different states of India must procure ILP (inner line permit) to enter the state. Similarly, non-Indians must acquire RAP (restricted area permit) to get an entry inside Arunachal. In this way, the Act has contributed in safeguarding the tribal culture and ethos. That is why the locals have time and again expressed their disapproval towards the practice of intermarriage between a tribal woman and a non-tribal man as there have been instances of such couples purchasing lands and registering them in the name of the former, so that the latter is free from all legal charges for using the lands for residential or commercial purposes. The second cause for resentment against such intermarriages is the availing of the benefits reserved for the scheduled tribes by their children, as in many cases they are given the maiden names of their tribal mothers.

While this issue against non-APST offspring with ST certificate is taking its momentum, I lightheartedly recollect one evening in Khinjili, when a senior professor had asked me and my colleague the question, “What unites you as an Arunachalee?” I had unwittingly responded, “FOOD.” He was amused with my response but not the least convinced. However, the recent cancellation of the Gau Dhwaj Sthapana Bharat Yatra only goes on to prove that maybe ‘food’ does unite us as Arunachalees, though at other times we may be bickering with each other on communal lines. In retrospect, I remember my colleague passionately positing that “the land of Arunachal evokes a sense of belonging in us and that is what unites us as Arunachalees,” but the professor was still not convinced. He had his own reasonsto disagree with us. His argument was that “we normally identify ourselves based on our tribe-based identity and not as an Arunachalee. We become an Arunachalee only after we cross Banderdewa.” That statement caught us off guard and yet we could not completely disagree with him. Maybe we do have fragmented identities based on our affiliations to our faith and tribe-based communities, but despite differences, one cannot overlook the fact that the geography does play a significant role in uniting us. This geography, which is our home, has its own diverse spatial politics on play. We are all influenced by these politics and we also do influence them. Thus, ‘home’ is not a simple term. It is way more complex than we can imagine. (Dr Bompi Riba is an assistant professor in the English department of RGU. She is also a member of the APLS and Din Din Club.)