“The evil that men do live after them,

The good is oft interred with their bones.”

– Mark Antony (in Julius Caesar)

When we read the above quotation on a spring morning in 1988, Dasu asked the class to pause. “Mark Antony was wrong and overstating his case”, he explained. “The truth is, it is difficult to speak ill of the dead, and we often end up saying good things about them.”

In his quintessentially sharp way, he left us all with a morsel of truth that is both universal and apt. The quote above was part of the literature textbook we had to read for our ICSE exams at the end of the year. Many will remember the bare facts of William Shakespeare’s play about the tragedies that befall those seeking absolute power and those trying to prevent the former from doing so. In the early sections of this cautionary story, Caesar was assassinated by his detractors, including his friend, the senator Marcus Brutus. With Rome in turmoil and the people confused, both detractors and friends of Caesar sought to persuade the masses that they were right. Brutus appealed to the people’s sense of democracy and justice by explaining why Julius Caesar had to be killed logically.

On the other hand, Mark Antony used passion, emotion, and exaggeration to persuade the masses that Julius Caesar’s killers were traitors who needed to be challenged.

Other teachers may have left it at that. They would have asked us to move on to the next stanza to tackle yet another sermon that followed the killing of a Roman dictator, so far removed from our time and context. Dasu couldn’t leave things as they were. For him, it was always necessary to peer through the surface, look deeper and reflect on the hidden message. Such teachers are rare because they have patience and compassion. Why would any of this Shakespearean stuff matter to those growing up at the cusp of changing times?

In retrospect, Dasu prepared my cohort and me for the world we would inherit from our parents in two significant ways. The first had to do with computers. We were the first batch to try our hands at the computers that St Edmund’s had acquired in 1987. We were divided into two batches when we reached Class 10 (in 1988). Those who chose computers were allotted to Class 10A, and those who decided to select commerce were allotted to Class 10B. I had no doubt where I wanted to be, so I wrote to Dasu over the winter, promising him that I was serious about computers and would work on a project during the holidays. He was always dubious about my intentions and ability to work hard, so he asked me to choose commerce when my turn came.

The Class of 1989 was the first to take a paper in computer sciences for our ICSE. That paper was made more accessible because Eric S. D’Souza wrote the prescribed textbook, Chipping In. What a class it was! We did not know it then, but somewhere between Boolean Logic and BASIC, we were scratching the grounds of a new landscape that would change our planet (and us) forever. It is not surprising that many of my classmates are beneficiaries of that first moment we were given access to the keys that would unlock the Information Technology revolution at the turn of the 20th century.

Dasu’s second contribution was to force us to slow down and look inward, especially when we were forced to grasp outward things in a rapidly changing world. A few years after we left school, the world’s political, social and cultural landscape would change following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the liberalisation of the Indian economy. The certainties that our parents were used to, like government jobs, being frugal and navigating a moral world where right and wrong were marked out, were not there for us. We had to gasp for breath at the pace of change and hope our decisions would be correct. This heady world also meant we did not have time to look out for others. We were constantly being told to be better consumers and achieve impossible goals by advertising messages in the mass media. Dasu, with his deceptive depth of expressions, had always asked us to slow down and appreciate all the things we risked missing out on in our rush to join the rat race. He asked about our girlfriends, argued about football teams, pushed us into singing practice for the concert, and alerted us to the harsh truths we would encounter as adults. “If you slow down, Barbs, you see everyone left behind in the race,” he once told me before he scolded me for one of my many transgressions. Those who were left behind were often our allies and comrades.

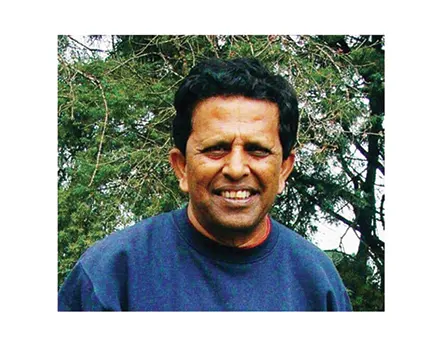

My friends and I are joined in grief at Br. D’Souza’s passing. Nilanjon Gupta, Angshuman Paul and I were fortunate to visit him on his birthday last year. We prayed for him standing around his bed, spoke to him about our lives, and cracked a few jokes while there. I know he could hear us, for there were times when he chuckled at some outrageous comment (one had to do with his favourite footballer, Michel Platini). In our sadness, we also realised that he created a new world for us. He gave us a few handy tools and rules to inhabit and navigate this world. The tools were simple: poetry, art, sport and a good dose of unmalicious gossip. The rules were more straightforward: look out for each other, especially those falling through the cracks.

Travel well, Sir. We have nothing but good things to remember at your funeral service. See you on the great big football field or concert hall up in the sky.

– Sanjay Barbora (Barbs)

– ICSE 1989