TribalBookworms

[Dr Doyir Ete]

The pulse of a society is often gauged by how much it values art and culture and how these are respected and celebrated. It shows the society’s appreciation for beauty and its love for fine arts and literature. Recently, the capital saw interesting events hosted around such pursuits. The Arunachal Literature Festival (ALF), now in its 6th edition, successfully hosted litterateurs from around the world. The fest,held from 13-15 November at DK Convention Hall, Itanagar, has firmly established itself as a must-attendcalendar event. The festival offered a plethora of writers, novelists, poets, and dramatists providing literature enthusiasts with a surreal experience right at their doorstep, not to mention the vibrant display of books for sale, along with other delightful knick-knacks. The atmosphere itself felt like the breath of crisp papers, a haven for bibliophiles.

Adding to this literary feast, the Arunachal Rang Mahotsav (ARM), a theatre festival currently running from 22 November to 5 December, offers a brilliant lineup of performances by both local and international artists. The fest has already created buzz among the populace in its maiden voyage. In a world often inundated by fast-paced living, events like these offer a much-needed breather. I would like to offer a gentle reminder that while we navigate the daily demands of life, we must also engage with pursuits that nourish our mind as well as our soul. These pursuits, be it reading, writing poetry or even gardening, to list a few, must run side by side with our other worldly aspirations. Events like the ALF and the ARM in our state are indications of positive happenings, and now the onus is upon us to seize these opportunities of soaking in the beauty of art and literature. In turn, it will also boost the morale of the arts and artists of our state.

Recently, Rajiv Gandhi University was enthralled by two dramas, The Salt of Life and Lapya, which were performed to a packed audience. The Salt of Life, based on the oral traditions of the Tani tribes, stood out for its innovative experimentations, incorporating multilingual dialects, multi-tribal attires, and exceptional use of props. Directed by Riken Ngomle, his troupe delivered a brilliant performance, exuding confidence and powerful dialogue delivery. The drama opens with commentaries on contemporary issues that resonated deeply with the audience: the APPSC imbroglio, the stereotyping of Galo girls, the challenges of finding rents for Nyishis and Tagins in the ICR, dilapidated roads, and the selfie craze. The display of attractive traditional attires further enriched the drama, beautifully capturing the essence of Tani and Tibetan cultures. What struck me most was the depiction of Tani, the mythical forefather, portrayed as both a naughty trickster and a compassionate brother. Similarly, his brother Taro’s character drew mixed emotions — we feel anger that he is duped by Tani, but at the same time, we lose patience at his gullibility.

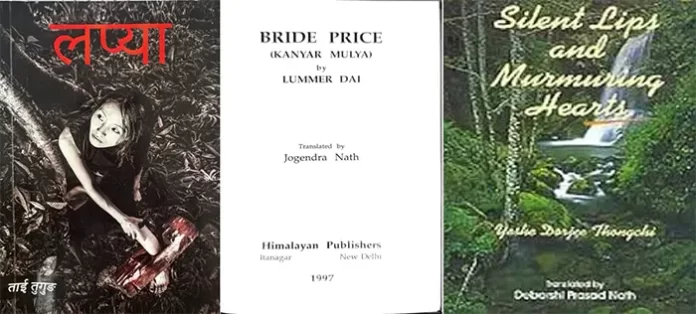

Lapya was especially heart-wrenching. The regressive practice of forcible imprisonment, depicted in the drama, thankfully no longer exists. The author ponders this practice and the plight of women, clearly critiquing both through his drama.Written and directed by the multitalented Tai Tugung, the dialogues are delivered in our very own Arunachali Hindi, with its tone and tenor reflective of everyday speech. This choice of language effectively captures the essence of lived reality, avoiding the defamiliarizing effect that might arise from the use of ‘shuddh Hindi’. Once again, the cast delivered a brilliant performance. The play assails the mind to confront the patriarchal biases of society that have trapped victims like Yama, the female protagonist, who tragically meets a violent end. There is no happy resolution for her, no space to navigate the oppressive social structures of her time.

However, in the story of another literary heroine, Gumba, whose plight is tangentially similar to Yama’s, the author offers his heroine a shot at a happy future. Gumba’s tale is narrated in Bride Price, a novel by the renowned Adi novelist Lummer Dai, offering a different perspective on women’s struggles within traditional societal frameworks. Lummer Dai, a visionary in many ways: a successful novelist, an editor and a social reformer, raised different social issues in his many novels. As said earlier, unlike Yama in Lapya, Gumba looks forward to a future where she can achieve her passions and dreams. Originally written in Assamese as Kanyar Mulya, the novel was translated into English as Bride Price by Jogendra Nath. As the title suggests, the story revolves around the practice of bride price, which is critiqued in the novel. It not only highlights regressive social practices but also emphatically advocates reformation of the society through education and development, with the youths playing a pivotal role. The narrative follows Gumba, a determined young girl aspiring to continue her education despite immense pressure from her family. Betrothed at the tender age of three, Gumba is forcibly sent to her husband’s house upon coming of age. She refuses to comply with this prearranged marriage, even starving herself to the brink of death. Subjected to imprisonment, physical abuse, and vilification, Gumba remains steadfast. Despite her father’s threats and being withdrawn from school, she continues her fight for self-respect and dignity.

What stands out to me, beyond the shared thematic concerns, is both the authors’ portrayal of their heroines as strong females. Here, I would like to dwell a bit on exploring the common strategies employed in reading such stories. These stories stem from the writers’s social consciousness and their desire to create awareness to uplift the lives of people. In these narratives, they vocalise the issues faced by women and their plight. So, clearly, these are stories with social issues. However, reading them solely through this lens is both limiting and parochial, as it reduces the stories to being just about social issues and, in turn, renders the heroines mere ‘types’ symbolising victimhood. The other aspects of their characters, such as defiance, resistance, and indomitability, become secondary. For example, the novel Bride Price is extensively discussed in literary discourse and is mostly defined as a narrative about the practice of bride price and the suffering it inflicts on women. However, Gumba’s fight, her beliefs and principles form the crux of the novel. She is the voice of the author himself. Focus must be given to this aspect, too. Similarly, Lapya is often interpreted narrowly through the lens suggested by its title. However, Yama and her fight against forced marriage is on a different level of its own. Her character in itself also demands more space and recognition.

Thus, the alternative ways of reading that can be explored foreground these protagonists as trailblazers of literary heroines from our state, given the dearth of such figures in the landscape of literary imagination. Even in our oral stories, male figures dominate, while strong female characters are often overlooked. As our state’s literature grows, we need compelling female characters to inspire more stories and enrich our literary scene. In such a reading of the stories, Gumba and Yama should not be seen merely as victims but as fighters – exemplars of courage and resistance. This perspective not only redefines their roles but also influences the way literature is consumed and interpreted. After all, the way a story is understood profoundly shapes how it contributes to literature as a whole.

There is another literary precedent — a namesake to Yama, who is also a victim of the custom of bride price. In the novel by YD Thongchi, Silent Lips and Murmuring Hearts, set in the 1950s and the 1960s, Yama, the heroine, is sold off in child marriage. As a young woman, she falls in love with a Sherdukpen boy, Rinchin, and becomes pregnant with his child. However, in the end, the lovers are forcibly separated, and Yama is dragged away by her husband and his clan brothers. The three stories use the trope of ‘social evil’ but lead their heroines to very different fates — death, freedom, and deprivation. This highlights the precariousness of women’s lives under such evils. The stories reflect the shared concerns of writers, all of whom highlight the practice of bride price as a central cause of women’s suffering in tribal societies like ours. The stories suggest that eradicating such customs is essential for achieving women’s empowerment.

These stories compel us to collectively ask: Has the practice of bride price truly been eradicated? Have women in our society been fully empowered? It is difficult to answer with an unequivocal ‘yes’. Bride price continues to be practiced in some areas, and other social evils still constrain many women in different ways. I am reminded of Bob Marley’s famous lines, “No woman, no cry”- a powerful reminder of resilience amidst hardship — a reality many women still face today. (Dr Doyir Ete is Associate Professor, English department, RGU. She is also a member of the APLS and Din Din Club.)