On Yeshe Dorjee Thongchi’s ‘Paharar Cha’

[ Dr Bompi Riba ]

Human nature is such that we take people, moments and things for granted, until they are no longer around. Oftentimes we don’t value the times that we have with our loved ones, only to regret later. This apathetic proclivity to be irresponsible towards them gradually seeps into a fragile bond and infects the affectionate hearts and renders them cold and detached. At times, we are mere puppets in the hands of circumstances and we move in whichever directions the strings are pulled, till they are cut off. It’s only in death that we inherit the meaning of a person’s life, particularly in relation to the oeuvre of his or her works. But the legacy comes more often not so as a gift but as something abandoned in death,and it is up to the ones left behind to make sense of it. A writer’s legacy is passed on in his writings, but what if the readers are not aware of these writings? Then they are as good as never having existed. Unfortunately, this tragedy was true, at least for the first-generation writers from Arunachal Pradesh, in the context of readers from their own state. Writers like Lummer Dai and Yeshe Dorjee Thongchi, who enriched the Assamese literature continued to remain unacknowledged in their home state for years mainly because of the language policy (1972) that replaced Assamese with English or Hindi

as the medium of instruction in schools, thereby leading to the production of a new generation of educated tribals who could not read nor understand Assamese. In the process the literary works of these pioneer writers succumbed to a perennial state of oblivion. Today we have a few translations of their works, both in English and Hindi. At least three of them are also included in the syllabi of Rajiv Gandhi University’s MA departments of English and Hindi. However, this has made it all the more imperative for translating the pioneer Arunachali literature, among which Lummer Dai had written at least five novels and Yeshe DorjeeThongchi has five plays, four collections of short stories, and eight novels to his credit.

Literature serves as a rendezvous between ‘what have been’ and ‘what could have been’. Usually, writers cultivate subjectivity consciously to create literature which is distinct from reporting. Both the mind and the heart come together for any creative composition. Certain event, person, emotions or even ideas serve as catalyst for a writer to work like a painter with different colours to finally produce a concrete image. However, it does not mean that literature is far from reality. The usual allegation against it is that it is all about fancy imagination, but paradoxically, there may be more truths in fiction than in everyday reality. To substantiate this claim, one can even quote HE Bates, who in his book The Vanished World: An Autobiography (1969) stated that “the business of writing fiction is an exercise in the art of telling lies… in making his readers believe his lies are truth but they are in fact truer than life itself.” The universality that literature depicts is more veracious than mere facts. For instance, one learns more about gender politics in Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, the problematic use of power in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, the futility of war in Ernest Hemingway’s Farewell to Arms, etc, to name a few. The literary revelation of human characters and other themes are more implicit than direct as in reports. Interestingly, no readers are neutral as they have their own individual baggage of experiences, ideologies and socio-cultural and religious backgrounds that work together to formulate their distinct interpretations, thus resulting with creation of infinite realities.

The Romanian-French playwright, Eugene Ionesco had once acknowledged that he had learnt about the social reality of the eighteenth-century France more from literature than other textbooks. According to him, “the genuine creator has a mysterious intuition of the concrete and particular truth which historians, sociologists and ideologies do not have” (Dostoevsky and the Age of Intensity). Therefore, this may be a simple truth that needs acknowledging that literary writers are adept at revealing human nature more than their fellow specialists. Yeshe Dorjee Thongchi’s short story Paharar Cha primarily deals with the traditional practices prevalent among the Nocte tribes of Laju, which permitted the already betrothed young girls to have intercourse with men other than their lawful husbands to test their fertility. It also questions the community’s socially recognised practice of infanticide of babies born out of such union. Chandra Bardoloi, who had joined the NEFA administrative services (now known as APCS) in 1965 as base superintendent, was the circle officer (CO) based in Laju in the 1975. In his memoir Call of the Blue Hills: Recollections of Arunachal Pradesh(2012), he has mentioned this custom that permitted young boys and girls to indulge in premarital sex to test the latter’s fertility, which was followed consecutively by the dreadful act of infanticides that were never reported to the administration. Parul Dutta in his The Noctes (1978) provides an ethnographic report of the aforementioned community, and explains that the abovementioned traditional custom is known as yawn-pangmi and the child that is conceived out of such practice is called pamtsa. He also explains that the root cause of the origin of yawn-pangmi was the practice of selecting brides for young infant boys, who will have to pay bride-prices as adults for marrying their brides. Since it would often take time in managing the bride price, marriages often got delayed. Therefore, in order to tackle the sexual onslaught of puberty, this particular system was commenced.

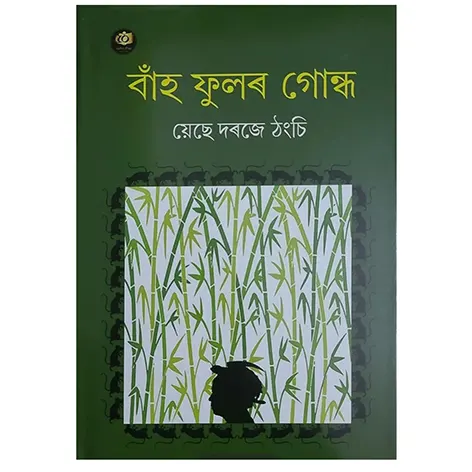

While Bardoloi’s Call of the Blue Hills: Recollections of Arunachal Pradeshand Dutta’s The Noctes report about the practice of yawn-pangmi, Thongchi’s Paharar Cha depicts the possible impact of the custom on the people of the community. It was first published in the Assamese magazine Prantik. It was published again in 2005 as one of the short stories in Thongchi’s collection, Baanh Phoolar Gondha. It has not yet been translated into English. However, I had the privilege of reading its unpublished Hindi version. Though crude, I would like to express my gratitude to the translator Inu Das, a teacher and an active member of the Arunachal Pradesh Literary Society for making it possible for a non-Assamese reader like me to cherish the literary work of our pioneer writer. In gist, the story depicts the ordeal of Kamtok, who had questioned the practice of yawn-pangmi. Despite passing her higher secondary exam with flying marks from Ramakrishna Sarada Mission, Khonsa, she wasn’t permitted to continue her education because of the sudden death of her father. She belonged to the Nocte community of remote Laju village, which did not have any effective leaders to bring development in that area. Just like her, most of the youths remained unemployed and directionless. As a result of that, many also resorted to joining the militants in the jungle. At times, she also had longed to join the underground militants but she had restrained herself as she was married to Ronhang, who was a teacher at the government school in Laju. It was because of her marriage that she remained constantly under the panopticon gaze of the society, particularly her husband, in-laws, and friends. Despite her marriage, she was still living with her family as she was yet to pass the fertility test, which would ensure her fit to consummate her relationship with her husband. So, before she took up the domestic responsibility of her husband’s house, she had to have intercourse with another man and conceive his child, who would be immediately put to death after his birth.

The education that Kamtok had received in Sarada Mission had greatly influenced her perspective, as a result of which she found the tradition of yawn-pangmi to be disgraceful. She was determined never to yield to the pressure imposed on her by her mother to spend the night at junpang (a dorm for young girls) and attend to the call of hot-blooded young boys. However, as fate would have it or her mother might have contrived it, she fell in love with Tukum, who was her brother’s friend and a member of the NSCN. On being pregnant with his child, she was considered eligible to take up the domestic responsibility of her husband’s house. When she was asked to consider the baby growing inside her womb as already dead even before its birth, she tried to convince her husband to resist the tradition by questioning his education. She even asked him to feel the movement of the baby by placing his hand on her belly. But when her effort went in vain, she decided to run away from home despite being heavily pregnant.

Unfortunately, on the day she planned to escape, she had her labour pain. She gave birth to a baby, who was immediately taken away from her to be killed. In an utter state of despondency, she had cried ceaselessly for her child, whose sex was also not revealed to her. However, to her surprise the conversation that she had with Ronhang had a lasting impression on him and he could not kill the baby. Instead, he stepped forward to embrace it as his own son. Thus, one notices how as a visionary, the author had limned the influence of education in defying the age-old practice of yawn-pangmi, which in due course of time was deemed abominable. Today, it is no longer in practice.

This particular story is a reflection of how literature mirrors not just the society but also a particular time. It is an illustration of how literature can serve as an alternative source for documenting history, society and its people. Pioneer writers like Lummer Dai and Yeshe Dorjee Thongchi lived and witnessed the different transitional phases of Arunachal, which were reflected in their literary works. The fact that the works of their contemporaries like Rinchin Norbu and Mosabi are lost in anonymity, it makes one realise in overwhelming desperation that we are deprived of these hidden gems (the literary works of the first-generation writers), and that we will continue to be deprived unless someone translates them for us. Until then, unfortunately, the first-generation writers’ tragedy of being in oblivion will continue. [Dr Bompi Riba is Assistant Professor, English Department, RGU. She is also a member of the APLS and Din Din Club.]