On anthropocentrism in Lummer Dai’s ‘Heart to Heart’

[ Dr Bompi Riba ]

In recent times the news about the alarming rise in incidents related to dog bites, the reported 117 cases in a week to be precise, and rabies-related deaths appalled the residents of Itanagar and Naharlagun. The social media also witnessed a state of frenzy as videos and photographs of dog bites circulated on various virtual forums, leading to panic among the residents. There were tweets of annoyed as well as genuinely concerned citizens appealing to the dogowners to vaccinate their pets and keep the aggressive ones on leash for the sake of the security of the general public. In the hullabaloo, a video of dead pet dogs killed by their owner in their bid to become responsible citizens also surfaced on social media platform like Facebook. In a turn of events, the gaon buras of Bam village on 18 May took a resolution in a keba (meeting) to eliminate dogs from the village within a week as a preventive measure. They also proposed to engage the youths of the village to kill the dogs. In contrast to that, the youths in the capital city started an initiative called ‘Arunachal Dog & Cat Rescue’ for rehabilitating stray and abandoned dogs.

Meanwhile, I also became a witness to my son being bitten by a dog in an unprovoked situation. My initial reaction was of shock, which was followed by an immense rage which led me to hurl stones as well as curses at the dog. After having washed the wound and getting my son vaccinated, I confronted the shopkeeper who was the owner of the dog. He was a young boy who was really apologetic for his pet’s behaviour. So, when he produced the vaccine cards of his dogs, I let him off on the condition that he keeps his pets, five in total, that could be seen either lying on the passage used by the customers or on the open space near the shopping complex. However, this incident compelled me to ponder on how a normal person would react if his loved ones succumbed to dog bites. While contemplating on this issue, I came across a Facebook post in which a man lamented over the death of his four years old German Shepherd, Blackie. The disturbing fact about that post was the remorseless admission of the rider who had hit the dog intentionally to kill it. These incidents prompted me to choose Lummer Dai’s Heart to Heart (2021) for this edition of Tribal Bookworms, where the author dealt with a similar situation.

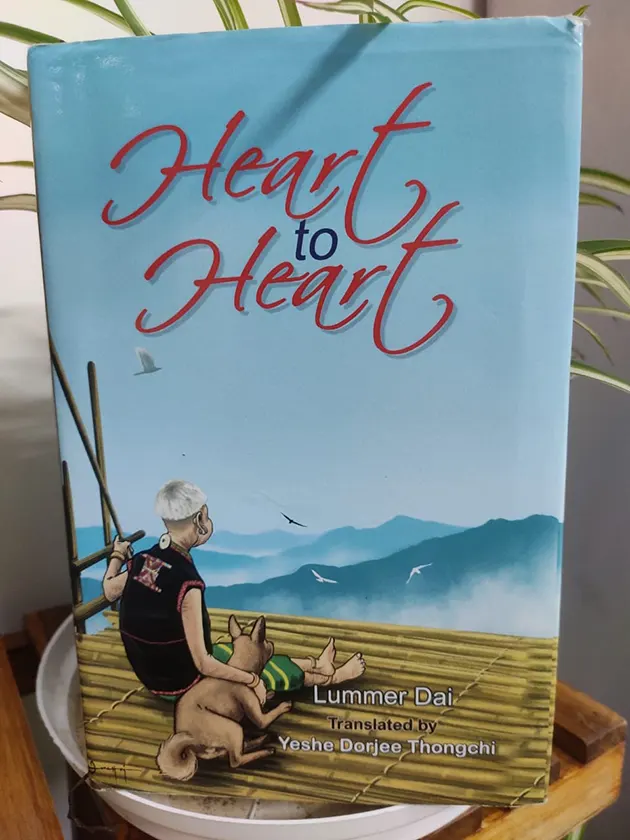

Though the subject of the abovementioned novel is local, it has a universal appeal and, apart from thehuman-animal dichotomy, it also tactfully presents the conflict between other binaries, such as traditional/modern, science/superstition, man/society,etc. It was originally published in Assamese as Mon aru Mon in 1968, and its English translation was done by Padma Shri awardee Yeshe DorjeeThongchi, who also credits Lummer Dai as the first Arunachali literary writer. As per the school record, Dai was born in 1940. He was among the first generation of school-going students from his village, Siluk, where in 1948 the villagers dared to construct and establish the first school in NEFA (North East Frontier Agency). However, due to lack of economic support, the school closed down within a year and Dai took admission in the government middle school in Pasighat, where, for the first time, he got acquainted with Assamese literature. It was there that he wrote his first article, Aborar rog nuguse kiyo, in which he had expressed his concern over the unhygienic lifestyle of the Abors which was the root cause of frequent illness among them. At a very young age he had shown his potentiality as a writer with a mission who responsibly dealt with issues of his tribal society. His five novels, viz, Paharar Hile Hile, Prithvir Hanhi, Mon aru Mon, Konyar Mulyaand Oper Mahal delved in various social practices prevalent in his contemporary times, such as the slavery system in the Adi society, the role of kebang, the practice of bride-price in the Galo society, etc, to name a few.

Lummer Dai was a visionary writer who wrote about issues that are still relevant in the current times. In Heart to Heart, his personality is replicated through a fictional character, who is, in fact, called by the author’s pet name, Badang. In various instances, one can perceive his inherent disposition towards reforming the society that he belonged to. His persistent appeal for proper medical treatment for both men and animals, despite the villagers’ resistance towards doctors and their prescriptions,can be taken as one of the examples. It is also to be noted that the Adi society that Dai depicted in this novel is different from the current times. The villagers in the novel were bereft of modern education. So, it was natural for them to be susceptible to superstitious beliefs. Almost everything in the community, whether it was good fortune or misfortune, was attributed to the spirits,and sacrificial rituals were performed to either appease or thank them. The overall ambience of the society was that of superstition and there were a lot of taboos practiced as a consequence of that. Badang dared to defy these taboos because of his conviction in rational outlook and also to prove to his elders that nothing happened to him despite him not observing them. Through his character, Dai represented the educated generation who were ready to shoulder the responsibility of their society.

Apart from Badang’s effort to reform his society, the narrative of the text centered on human-animal relationship, for which one of the most neglected subjects in literature, ie, the life and challenges of an octogenarian, was depicted with utmost care by the author. He empathetically portrayed the character of an elderly Adi woman, Gidum, who lived all by herself in the village as she had no living family members by her side. Through her character, Dai sensitively presented the lonely life of old people. In Gidum’s case, her only companion was her pet dog, Bomong, whom she treated like her own grandson. At the very outset of the novel, she actually expressed her concern for his life as she was aware of her impending death owing to her old age. She worried as to what would happen to him in case she died before him. But as a consequence of an untoward incident, he became a victim of their neighbour Sangam’s wrath, who killed him by shooting for fatally wounding his son, Gamling.

That unsettling event caused trauma to both the deceased boy’s family and Gidum. In the case of the former, it was a natural reaction to be angry and vengeful, while the latter was heartbroken for having lost someone who was like a grandson to her, though to others he was only a dog. Dai had sensitively presented the pain, anxiety and loss of both the parties without any prejudice. However, in the narrative, it has been observed that, even among the villagers, there were some rational and kindhearted ones who empathised with the old woman for her loss. They could perceive that the dog’s way of expressing his love for the old woman was by watching over her house in her absence. In fact, the incident that led to Bomong attacking Gamling was when he found that the latter was stealing guavas from his Gidum Nane’s garden. He was simply fulfilling his duty, although it is also a fact that he did not differentiate between a child and an adult. On top of that, by virtue of being a dog, he was also being territorial in nature. However, Sangam considered him an inferior species and he could not understand why the old woman treated him like a human being,as in most cases the paradigm of relationship status between dogs and their owners is that of the masterand slave. Therefore, this deliberation makes one wonder if dogs, or for that matter animals have any sense of ownership of their body, or for that matter their life as human beings do.

Human bodies are markers of their race that tag them to the geographical areas of their origin and the expected socio-cultural behaviour. They own their bodies, unless due to varied circumstances, they are enslaved by someone. Otherwise, as free beings they are at least conscious of their right to not be killed or assaulted arbitrarily. They also have the privilege to own animals, which in turn give them the power to exercise either malevolent or benevolent acts towards them, depending upon the circumstances and, at times, their temperaments too. Human civilisation is guilty of uncountable ritualistic slaughters of animals for propitiating or appeasing gods or spirits. One of the prominent qualities that distinguish them from animals is their ability to use complex language and to communicate complex ideas thereby. Animals also communicate by crying and gesturing. However, their form of communication may seem insignificant in front of human’s language, which encompasses all of their experiences. In this context, it also becomes pertinent to discuss the concept of ‘anthropocentrism’, which literally means ‘humans as central entity’ of planet Earth. Almost all of human societies practice cultures that are anthropocentric in nature, which in turn endorses the idea that all other entities such as animals, birds, natural resources, etc, are there for the benefit of mankind. So, basically everything in this world is supposed to serve the purposes of human’s existence.

Generally, in our attempt to define culture, we tend to consciously or unconsciously draw a line between man and animal. To illustrate it, we can take a simple example of the characteristic opposition between the concepts, ‘humanity’ and ‘animality’, which is condoned by the human society. In other words, the human species is considered superior over other species, like animals, mainly because of culture, which distinguishes corporeity and instincts as typical animal characteristics. Humans also have these qualities but the saving grace for them is culture, which prevent them from becoming like animals. In other words, culture is often considered an antidote to animality, which is also associated with violence and disorder. Man is forever struggling to elevate himself from everything that is associated with the feral state as animals represent the negative qualities of man. This is the common perspective which is also responsible for our understanding of what is humanity, culture and animality. Thus, in conclusion, it becomes inevitable to question if Bomong or Sangam represented humanity or animality because the actions of both of them were driven by sheer love for their loved ones. (Dr Bompi Riba is Assistant Professor, English department, RGU. She is also a member of the APLS and the Din Din Club)