TribalBookworms

[ Dr Bompi Riba ]

If not for oppressive experiences and challenges, most adults would definitely hold on to their childhood nostalgically. For most of us, children’s books, such as Tinkle digest, Grimms’ Fairy Tales, etc, have often been our private delight. Though we are adults now, there still is a tendency in us to read them, simply as a child would, without really being bothered about the possibilities of the influence of the ideologies permeating in these books. A general misconception about ‘children’s literature’ is to consider it a simple and non-problematic genre where a reader can actually guess what to expect. It is in fact more complicated, and yet it is one of the most taken-for-granted bodies of literature. It is commonly understood to be specifically dealing with materials written for the sake of children and young adults. Occasionally, there have been debates on the suitability of certain subjects for the juvenile readers. Questions such as whether the contents are too terrifying or insinuating explicit sexual behaviours, or confusing young readers with ambiguous moral lessons, etc, do come up for debates. Apart from the subject matters, in academia, the style of writing is also brought under scrutiny to assess if the grammatically incorrect sentences or colloquial expressions such as swear words or abusive and derisive language used on the pretext of experimental writings are causing more harm to the young minds. This further directs our observation towards the inconclusive classification between adult literature and children’s literature. To illustrate, one can look at the case of books like the Harry Potter series, which were originally published as children’s literature, but they also have huge readership among the adults. Therefore, one wonders what exactly children’s literature is.

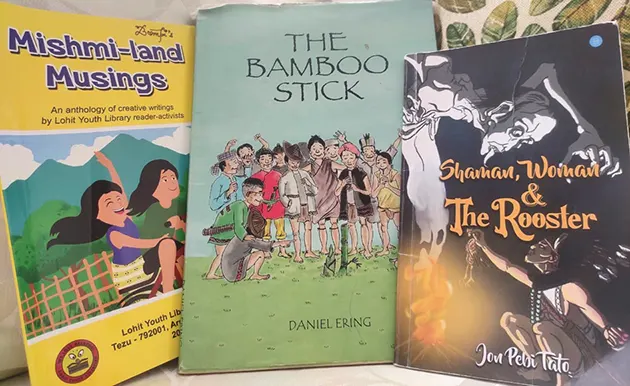

Generally, all folktales, myths, legends, ballads, fairytales and even nursery rhymes come under the umbrella of ‘children’s literature’. Today it has expanded and even encompasses e-books, computer games and fan-fictions too. One has to understand the significance of this particular genre because they often become gateways for children to see and understand the world around them. There is also no doubt that they become mediums through which children learn new vocabularies, but one cannot ignore the fact that they contribute towards shaping their mindsets and attitudes too. Therefore, seldom is there any children’s literature that does not impart education of some sort. For instance, the beginning of Jon Pebi Tato’s Shaman, Woman & the Roosterexhibits in a subdued manner the use of the classical motif of women as the central cause of problem for men. Just like Eve in the Genesis chapter of the Bible disobeys god’s command regarding the forbidden fruit, leading Adam to do the same, Yami, the female protagonist of SWR disobeys the village leader Ming Keng’s instruction to stay put in their hiding place until the time is appropriate for them to approach the great shaman of Gong village. Being smitten by the shaman’s appearance and his demeanour while performing the shamanistic rituals, she walks towards him without thinking and disturbs the ritual. Her brother, who runs towards her to protect her, gets caught by the uyu or the spirit along with her. This evidently becomes the cause of the adventurous journey in the story. While the obvious message from this episode is related to how disobedience can lead to terrible consequences, the patriarchal notion of women being more impulsive can also be construed. Having said that, I would like to point out that,despite a few more archetypal observations and flaws in terms of the structure of the narrative and characterisation, Jon Pebi Tato’s creativity in drawing elements from folklore has invigorated the literary scene of Arunachal Pradesh. This particular text exhibits the hybridisation of the tradition of the oral and the literate. I personally like the section that incorporates the style of folktales in highlighting the reason behind the growth of cockscomb on a rooster and its morning routine of crowing “cock-a-doodle-doo.” However, it would have been better if he had used the more local onomatopoeia “cocko-re-ko” instead of the popular English sound for the cock’s crow. Nevertheless, the notable growth of the writer in his second book, Shaman and the Secret Spirits of the Past is commendable. Some of the imageries in this sequel are exceptionally vivid. In due course of time, I shall take up this text as well in Tribal Bookworms.

A gem of a children’s literature from Arunachal would be the graphic novel, The Bamboo Stick, by Daniel Ering. As characteristics of this genre, it combines words with visual images to target the young children as prospective readers, whose experience in life is relatively less. Consequently, their perspectives about themselves, others and the world are still developing. In a situation like this, graphic novels like The Bamboo Stick serve the purpose of integrating the young children into the ideology of tribal culture. It incorporates oral narratives as one of its central features with Abu Tapon, an elderly man, narrating the story of 26 brothers from an Arunachal village and their ordeal to young children. An adult can easily identify that these 26 brothers represent the major tribes of our state. But for a native child, the images would simply bring out pure delight on seeing characters in attires that they are familiar with. Despite the use of no critical engagement, the child can empathise with the Arunachali brothers in captivity and rejoice in the small victories they achieve with the use of their ‘green gold’, ie, the bamboo and, ultimately, their freedom. I hope more such literary works come out from our state. In fact, it is also a personal appeal to the author, Daniel Ering, who has maturely handled the plot of the story by promoting the spirit of universal brotherhood.

Children’s literature also reflects on social phenomena. The writers of Mishmi-Land Musings: An Anthology of Creative Writings, who are also addressed as the ‘Lohit Youth Library Reader-Activists’, encapsulate the essence of what it is to be a child. Most of the stories emanate with blissful laughter, whether it is because of a painful and yet a joyous bus ride or about children mistaking a root of a tree or a black rope for a snake, or simply falling off a bicycle into a roadside ditch. Children love sound effects in storytelling. One can actually grasp their attention by making all kinds of weird and yet relatable sounds. This anthology is also filled with interesting sounds like ‘dong, dang, dong’, ‘DONGG’, ‘DDHaam’, ‘Aaahh! Yoooo…Ohhh!’,‘Chhaak’, ‘Thaaang!! Thaang’, ‘tat, tat, traat, trhrhh’,and expressions like ‘Aya!’ ‘aiyaa’. Mundane events like siblings fighting over a TV remote and making up as quickly as the blink of an eye; waking up after a nap in the noontime and actually thinking that you are late for school; or a dog biting your finger on being teased; or a child sleeping inside an almirah to the terror of the family members; or a granddaughter panicking because she thought that her grandmother has disappeared in the maze of the shrubs and herbs,etc, are the subject matters of these stories. One story that exceptionally stands out for me is A Story for Mother by Asuni Khamblai, which basically is a dream of a child witnessing violence at home caused by a drunken father. It can be taken up as a representative text that portrays the trauma of a child growing up in an abusive environment and the wistful longing for a happy family. Another story that deals with similar issue is Waiting for Mother by Shapilu Rangmang. It also reveals subtly how a child suffers emotionally as a result of broken marriages.

Children’s literature is an enticing area of study, but in our state it is in a nascent stage. We have a few illustrations of folktales and countable literary-folksongs. We need more writers to experiment in this area. Hopefully, in the days to come, our children will have more options of reading and discussing stories that talk about them and also introduce them to our tribal worldviews. (Dr Bompi Riba is Assistant Professor, English Department, Rajiv Gandhi University. She is also a member of the APLS and Din Din Club.)