[ AN Mohammed ]

As per reports, China’s development activities,mainly construction of hydroelectric projects on the Tsangpo, are primarily to raise the standard of living in Tibet, to manage fresh water scarcity, and to support China’s goal of reaching a carbon emission peak before 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060.

(Photo: The Diplomat, November 2019)

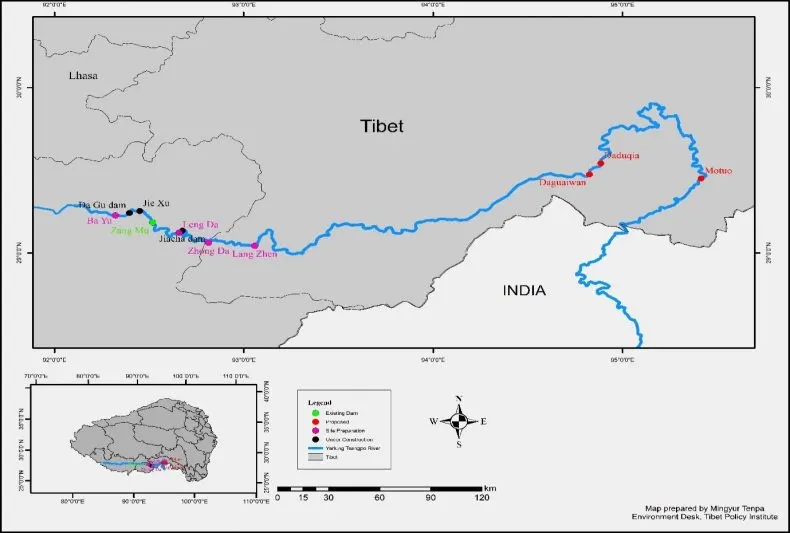

China has been secretive about plans to dam the Tsangpo and announced that a five-dam cascaded hydropower projects – Zangmu, Gyatsa, Zhongda, Jiexu and Langzhen – would be initiated to the east of Lhasa. The 116 mtr high, 510 mw Zangmu dam on the mid-reaches of the Tsangpo, located in a gorge 140 kms southeast of Lhasa, at an altitude of 3,260 metres, started generating power in November 2014. The 360 mw Gyatsa (Jiacha) dam was completed in August 2020, and construction is underway for the 560 mw Jiexu dam.

Close to the Zangmu dam, three more dams – 640mw Dagu, 71 mw Bayu and 800 mw Zhongyu – above the Great Bend, on a tributary known as the Yiwong river, are in advanced stage of planning.

2.7 km elevation before entering Arunachal Pradesh

China is also planning its most ambitious, and the world’s largest hydropower project – the 60,000 mw Motuosuper mega dam – on the Brahmaputra’s barely explored Great Bend, a stunning canyon where the river drops fiercely over 2,700 m within a 50-km stretch before it changes course towards India. It was also reported that China would divert the Tsangpo water from the project to its northern arid region. The announcement immediately sparked concerns among Indian analysts who suspected Beijing of harbouring ulterior geopolitical motives and asserted that the diversion could have negative environmental consequences, including reducing the flow of water into India as well as possibility of creating artificial floods.

Current status of the water disputes: Hongzhou Zhang in WIREs Water, 2015, stated that “the Brahmaputra river, shared by China, the upper riparian state and India, the middle riparian state, is among the shared rivers where most tensions exist. This is due to three major reasons. First, China occupies over 50% of the Brahmaputra river basin area, for which the potential impact of China’s activities on the Brahmaputra river is much bigger.

“Second, the Brahmaputra river is of great importance to both India and China. For India, it accounts for nearly 30% of the freshwater resources and 40% of total hydropower potential of the country. In case of China, while at the national level, the Brahmaputra river’s role in the country’s total freshwater supply is quite limited, it is of great importance to Tibet. The Brahmaputra river is considered the birthplace of the Tibetan civilisation and it plays a critical role in Tibet’s agricultural and energy sectors.

“Third, the Brahmaputra river is linked to Sino-Indian border disputes. This disputed area is called South Tibet in China and Arunachal Pradesh state in India, which now controls the area. This disputed area occupies about an area of 83,743 sq kms and has a population of over 1.5 million people.”

China does have a track record of relying on mega-infrastructure projects such as the world’s largest hydro project – the 22,500mw Three Gorges dam and the South-North Water Diversion (SNWD) project – to transfer 44.8 billion cubic metres of fresh water annually from the Yangtze river in southern China to the more arid and industrialised north through 1,264kms long three-canal systems to deal with its water challenges.

In relation to transboundary river cooperation with neighbouring countries, China is one of the three countries – the others being Turkey and Burundi -that voted against the 1997 UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Use of International Watercourses (UNWC). China is the largest producer of hydroelectricity in the world. Dams in Yunnan on the Mekong river have worried lower riparian countries Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, who have set up a joint inter-governmental Mekong River Commission (MRC) for joint management of shared water resources. However, China remains absent from the commission.

India’s plan for hydropower development on Siang:

What really worries India the most is China’s water diversion plan at the Great Bend, which could let the Siang river run dry, thus threatening the survival of hundreds of millions in the downstream.

Based on river basin data, it is easy to reach the conclusion that the potential impacts of Chinese flow diversion could be huge, considering the fact that 50% of the river basin of the Brahmaputra is in Chinese territory. The capacity of a hydropower plant depends on the water availability and the height of flow to the turbines. With the scanty quantity of water availability, a 60,000 mw project is possible in Tibet because of utilisation of the tremendous drop of 2700 mtr available at the Great Bend of the Brahmaputra.

In the event of diversion of the Siang river, the most affected areas will be the 150-km reach of the river from the India-China border to Pangin, where major tributary Siyom river joins.

In sharp contrast to China’s rapid development activities on the Tsangpo, India has not utilised the water of the Siang river till now, thus weakening its riparian rights in the international forums for river water sharing. China’s proposed 60,000 mw dam in Medog could reduce the natural flow of water in the Siang in India during lean patches, or trigger artificial floods in monsoon, which is a matter of concern to India.

To counter any potential misadventures by China in the Brahmaputra river, India proposes a 11,000 mw hydropower project on the Siang river in Arunachal’s Upper Siang district. The design of the Indian project includes a “buffer storage” of over 9 billion cubic metres of water during monsoonal flow. This could act as a reserve for water normally available from the Siang for water security, or protect downstream areas of Arunachal and Assam against floods due to sudden releases of water from the Chinese mega project.

Like in most of the countries of the world, water scarcity already prevailed in other parts of India. Due to climate change, scientists have predicted water scarcity in Northeast India in the near future.

China’s response toward India’s complaints about China’s ravenous exploitation of the Tsangpo river has been mild. On the other hand, the CNA analysis & solutions in a study titled ‘Water resources competition of the Brahmaputra’ in May 2016 mentioned that “China has concerns that India’s dam building activities downstream could further strengthen New Delhi’s ‘actual control’ over Arunachal Pradesh.”

Global warming, irrespective of any geographical or political barrier, is threatening human existence. The global countries are unitedly fighting the eminent disaster. The carbon emissions from the thermal power plants are mostly responsible for global warming. India committed to achieve carbon neutrality by 2070, while all advanced countries of the world committed to reach carbon neutrality by 2050 and China by 2060.

Electric energy, a yardstick of development of a country, needs transition of generation from thermal to renewable energy. Hydroelectricity being sustainable and cheap renewable energy, warrantsdevelopment of hydroelectric projects. Arunachal alone has a hydropower potential of 50,328 mw -40% of the country’s potential, whereas only 1,115 mw (2.21%) is operational.

International media reported, “Dam building has been an extremely slow and limited process in India, largely due to obtaining various statutory clearances,especially environmental and forest clearances, civic opposition to some dam construction, as well as financial constraints. This situation stands in stark contrast to the robust dam building on China’s portion of the upper Brahmaputra river. Despite India’s intention to build its own dams to manage water flows, the number of dams actually being built is extremely limited.”

In the construction of China’s 23,500 mw Three Gorges dam, 12 lakhs people were displaced without any resistance. But opposition from displaced people for creation of reservoir in hydroelectric projects is a real challenge in India. No one in this world wants to leave their own home and village where they are born and brought up with their families. There had been significant movements in the past by the displaced people due to the construction of the Tehri dam in Uttarakhand in 2001 and the Sardar Sarovar dam in Gujarat, constructed on Narmada river, that started in 1987 and was fully completed in 2017.

The Idu Mishimi community of Dibang Valley district had opposed the 2,880 mw Dibang multipurpose project for inadequate compensation for the project affected people and probable environmental impacts of the project during 2007-2011. However, with the induction of the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, people are satisfied with the compensation packages and have realised the benefits of hydropower projects for local people, as well as for the state.

Like all other developmental work, hydroelectric projects may have adverse impacts on the environment. The Environmental Protection Act,1986, and subsequent notifications from time to time have taken care of the environmental impacts to be minimised during construction and operations of the hydroelectric projects. The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, (also called the Land Acquisition Act, 2013) gives fair compensation for land and rehabilitation and resettlement to the displaced persons. The Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980, ensures conservation of forests and its resources by the compensatory afforestation for forest diversions, so that the environment gets minimum impact due to the construction of dams. The Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, amended in 2006, provides for protection of the wild animals, birds and plant species to ensure environmental and ecological security. The Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2006, protects the rights of the forest dwelling tribal communities and other traditional forest dwellers to forest resources, on which these communities were dependant for a variety of needs, including livelihood, habitation and other socio-cultural needs.

The 2022 manual for land acquisition in Arunachal Pradesh published the district-wise and category-wise land rates for land acquisition. The government should make the project-affected people aware of fair compensations, rehabilitation and resettlement provisions and compensatory afforestation programme for minimum environment impact.

After China (23,841) and USA (9,263), India ranksthird globally with 5,254 large dams in operation,while 447 dams are under construction. Most of these dams displaced millions of people. Overcoming the emotional factor of leaving ancestral houses, villages, and towns to resettle in new habitations, the project-affected people ought to cooperate with the government in dam building for all-round development of the state and the country. (AN Mohammed has over 40 years of extensive experience in the hydropower sector. He has been associated with planning, investigation and construction of various hydropower projects across Northeast India and retired as vice president of Reliance Power in 2018. Since 2019, he has been a consultant for hydroelectric project development in the NE region. He has authored over 50 papers on hydropower and flood management, published in national and international journals.)