TribalBookworms

[ Dr Bompi Riba ]

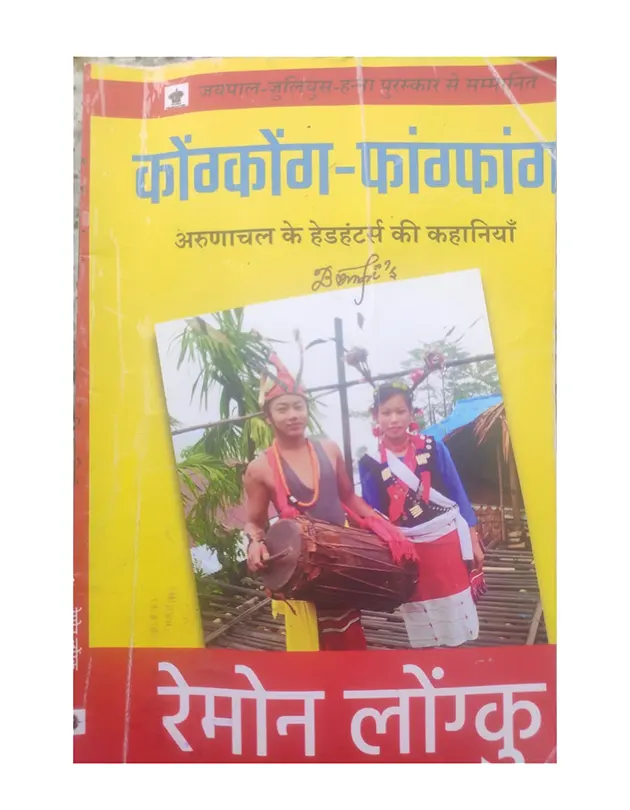

How many of us would agree with Socrates, who in his Phaedo, also known as On the Soul, remarked that a true philosopher always pursues death? The popularity of this view may be unlikely but there is no denying the fact that ‘death’ is an unavoidable subject and philosophising about it has yielded various reflections on not just the metaphysical aspects of death but also on life. While philosophers have argued deeply whether there is life after death or for that matter if the fear of death is rational, Ramon Longku’s Kongkong Phangphang: Arunachal ke Headhunters ki Kahaniya (2022) deals with gruesome deaths and accompanying emotions of fear, loss, despair, and anger, among others. This is the first collection of short stories from Arunachal Pradesh that centres around the Tangsa tribe of Changlang district. This tribe is also spread out extensively in Tirap and the Namchik river basins along the Patkai range. The term ‘tangsa’ is a combination of two syllables, namely, ‘tang’ and ‘sa’, meaning ‘hill’ and ‘people’, respectively. There are around 35-40 sub-tribes of the Tangsa tribe, each distinct from each other in terms of dialects, traditional attire, taboos and other practices, but there are also some sub-tribes that have similar customary practices and their dialects are also mutually intelligible. Traditionally, they were followers of animism, but in due course of time, many got converted to Christianity and some even became Theravada Buddhists. However, there is a section among the Tangsas, particularly the Longchang and the Muklom sub-tribes, that are ardent followers of Rangfrah, whose resemblance to Shiva, the Hindu god has been a matter of contention in the academia.

While the mores and the challenges of the Tangsa community are efficiently depicted, the predominant theme of this collection of short-stories is ‘death’. The author centres his first story around the traditional belief that reckless hunting might have fatal consequences because it grieves the forest spirits. While gory details of death are presented, the community’s beliefs and the death ritual that follow the unnatural deaths of characters like Rehap in ‘Ush Shikhar ka Shikhar’ and Rumi’s grandmother in ‘Dadi Aa Rahihain’ are worth mentioning. Such ill-fated deaths are considered as bad omen by the community and the dead bodies are cremated far from the village, usually in the unfortunate site of the event itself. And in the case of natural deaths, like that of Hoho in another short-story, the dead body is kept inside the kitchen on a bed made out of bamboo. It is also mentioned that the family and the relatives of the deceased pour water three times under the bamboo bed where the body is placed, but no explicit explanation is provided for that practice. Thereafter, the body is taken to the crematorium in a day or two along with his many cherished belongings. During that time the doors and windows of the deceased’s house are left open. The kitchen area is cleaned and any trace of fire in the hearth is also extinguished as there is a belief that the spirit of the deceased often returns to the village in search of his house and when he finds it empty, he leaves without turning back because he believes that he had entered the wrong house. But in case he turns his back to have a glance while leaving, then it is a sign of future calamity for the family. Interestingly, the custom of not turning back and glancing at the funeral pyre is also practiced among the living members of the deceased because of the belief that his soul may misconstrue the act as a longing sign of attachment, as a result of which he might follow them. However, it is to be noted that the author does not specifically mention the name of the sub-tribe that practices the abovementioned death ritual and taboos.

The book also projects the predicament of the community stuck in the political imbroglio as a result of the conflict between the Indian Army and the militants, whereby the innocent villagers when killed by the former are tagged as the latter, for which, the Army officers are not only applauded but also promoted to a higher rank. The story titled ‘Firing’ is a subtle attack on the practice of leveraging the death of innocent villagers for advancing in one’s career. Then, there is a story called ‘Dar’ which captures the fear of the villagers for the future of their sons. This story specifically describes the resistance of the villagers against the forceful kidnapping and recruitment of young boys by the militants. On similar subject is the story called ‘Phangthoi’, which depicts the utter helplessness and excruciating pain of a single mother whose only son is forcefully taken away by the underground people. I personally was touched by this story as it reminded me of one of my classmates from Tirap district, who went missing during the summer vacation of late 1990s. His story also resonates with that of Phangthoi.

Also worth mentioning are the two stories based on the community myth and legends, viz, ‘Shapitjhil’ and ‘Tingringparvatke Ush Paar’. The first story incorporates the narrative style of oral tradition where Mungtu, a college-going young adult, fascinated by the folksong sung by his maternal aunt, urges her to explain the story behind the song. The folksong recounts the legend of the Lake of No Return, which is located in Myanmar and is just 12 kms from Nampong town in Changlang district and can be seen from the Pangsau Pass. It is also infamously referred to as the Bermuda Triangle of India as several Allied aircraft flying over it mysteriously vanished without a trace during the Second World War. The locals believe in the presence of some unknown force there which might have pulled the aircraft into the lake. There are several legends associated with this lake and the folktale narrated by Mungtu’s aunt in the story is one of them. It can actually be considered as a cosmogonic myth that explains the origin of the lake. The second story, ie, ‘Tingringparvatke Ush Paar’, recounts the tragic fate of an abandoned village near Kuthung village in Namtok circle of Changlang district. Across the globe, there are folklores that talk about villages that were abandoned under mysterious circumstances. The common phenomenon observed in these legends is the outbreak of deadly epidemics which were often seen as the curse of supernatural forces that compelled the survivors to flee from there. This particular story is also no exception. It recounts the mysterious deaths of the villagers, which led to the desertion of the village which was believed to be cursed by the wrathful spirits of the past. It also reinforces the idea of how oral narratives blend history with myth to explain natural events through legends.

Last but not least, the two stories, viz, ‘Gardan Kaatne Wale Log’ and ‘Kongkong-Phangphang’, depict the now obsolete practice of ‘headhunting’ among the Tangsas. While the latter is mainly a love-story, the former focuses on tribal warfare and vengeance. In fact, the book opens with a prefatory note, in which the author expresses his opinion on the practice of headhunting among the Tangsas. According to him, it was never a core aspect of their culture but is an integral part of their community history. He also explains that it stemmed from vengeance, which the community resorted to for self-defense. However, Lowangcha Wanglat in his Headhunting Nagas of Arunachal Pradesh (2022) states that in dire circumstances, such as severe illness, family curse or mishaps, the Tangsas were known to carry out human sacrifices on advice of the tanwa or petang (the soothsayer). This practice is no longer observed today.

In conclusion, the young writer has demonstrated exceptional talent in narrating stories about his people and we can anticipate more such works from him. However, a few notable issues cannot be overlooked, viz, the presence of minor printing errors, likely due to human oversight, and incorrect punctuations in the narrative. These could have been avoided for a more seamless and flawless reading experience. (Dr Bompi Riba is an Assistant Professor in the English Department of Rajiv Gandhi University, Rono Hills. She is a member of the APLS and Din Din Club.)