[ AN Mohammed ]

Retreating glaciers

Glaciers, often referred to as the ‘frozen reservoirs’ of our planet, play a vital role in maintaining Earth’s environmental balance and sustaining life. These colossal ice masses, formed over centuries through the compaction of snow, are far more than frozen landscapes – they are a lifeline for ecosystems, communities and economies worldwide. The preservation of glaciers is not merely a choice but a global obligation. Their role in providing freshwater, regulating climate, supporting ecosystems, and protecting against sea level rise underscores their critical importance. As stewards of the planet, it is our responsibility to adopt sustainable practices to reduce carbon emissions and global warming to preserve the glaciers. By acting today, we can protect these majestic natural wonders for generations to come, ensuring the continued harmony and prosperity of life on Earth.

Climate change and global warming observed in Earth’s environment since the mid-20th century are driven by human activities, particularly fossil fuel burning which increases heat-trapping greenhouse gas levels in Earth’s atmosphere, raising Earth’s average surface temperature. Human-induced global warming is presently increasing at a rate of 0.2°C per decade, and is associated with serious negative impacts on the natural environment and human wellbeing, including melting of glaciers. To reduce carbon emission, energy transition from fossil fuel to green energy, India has taken decision to have renewable energy share of around 450 GW from solar and wind, while 70-100 GW would be from hydropower plants by 2030.

The challenges of Himalayan glaciers on hydropower projects

The Himalayan region, often referred to as the ‘Water Tower of Asia’, is a treasure trove of freshwater resources, primarily stored within its extensive glacial systems. These glaciers not only sculpt the landscape but also underpin the hydrological cycles that drive the mighty rivers of South Asia. Himalayan glaciers are both a boon and a challenge for hydropower projects. While they provide a steady water supply that fuels renewable energy generation, their vulnerability to climate change poses significant risks. Recognising and addressing these challenges through innovative engineering, policy reforms, and international collaboration will be key to ensuring sustainable development of hydropower in the region. The preservation of Himalayan glaciers, therefore, is not just an environmental imperative but also a cornerstone for energy security and resilience in South Asia.

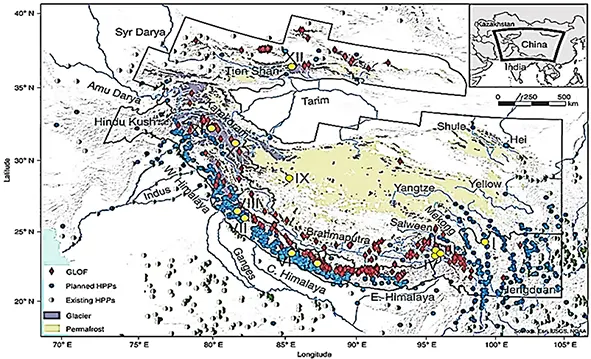

Glacial lakes are large water bodies beneath a melting glacier due to global warming. As they grow larger, they become dangerous because glacial lakes are naturally dammed by unstable ice or sediment composed of loose rock and debris. In case the boundary around them breaks due to excessive rainfall, avalanches, earthquakes, landslides, etc, huge amounts of water rush down the mountains, which could cause flooding in the downstream areas. This is called glacial lake outburst floods (GLOF).

There are an estimated 7,500 glaciers in the Himalayas and GLOFs have been associated with major disasters over the years. The 1926 J&K deluge, the 1981 Kinnaur valley floods in Himachal Pradesh and the 2013 Chorabari Tal glacial lake above Kedarnath outburst in Uttarakhand, killing thousands of people, are examples of GLOF-related disasters. Among the Himalayan states in India, Sikkim has more than 300 glacial lakes, according to the Sikkim State Disaster Management Authority. Out of these, 10 have been identified as vulnerable to outburst floods. These include the South Lhonak Lake and had been under observation by government agencies for years. However, disaster struck Sikkim on 4 October,2023 morning after the outburst of South Lhonak Lake, flooding the Teesta river that devastated downstream areas. The voluminous outflow destroyed the Chungthang dam of the Teesta 3 hydropower project and rendered several hydropower projects along the river dysfunctional.

Mega dams in Arunachal Himalayas

There has been growing concern among the masses and intellectuals over the safety of construction of mega dams in India Himalayan states, particularly in Arunachal Pradesh, where several mega dams are being planned, after the incident of the GLOF scenario in the Teesta valley in October 2023. Most of the glacial lakes present in Siang, Subansiri, Dibang and Lohit river catchments are present in the Chinese portion of these river catchments, which are far away from the project sites, hence posing insignificant threat of GLOF-induced flood.

The topographic, catchment characteristics, and glacial lake locations in the river basins in Arunachal are different, which indicates that there are no chance of GLOF-induced flood disaster for projects in Arunachal river basins as it was in the Teesta basin GLOF case. The glacial lakes are located far away from the dams, and, as a result of this, GLOF get attenuated to very low flood values. The slopes of the rivers in Arunachal are mild; hence the flow velocities of floodwater are lower and lead to higher travel time, allowing more time to take action to mitigate the effect of flood.

As per existing studies, the peaks of GLOF at dam sites are much lower than average monsoon flood for Siang, Subansiri, Dibang and Lohit basin projects. All the proposed dams in these basins are concrete dams, which are not vulnerable to failure. Due to the presence of large reservoir storage volume and provision for passing the flood through the spillways in the proposed hydro projects, the GLOF volume will be completely absorbed into reservoirs; hence no threat to dam or to the downstream population.

Glacial lakes present in the Siang river are located far away in the Tibetan plateau of the Siang river catchment. The slope of river Siang from some large glacier lakes up to proposed Siang upper dam site is of the order of about 1 in 150. Also, potentially dangerous lakes are located at about 500 kms upstream of the proposed Siang upper dam. The reservoir capacities at FRL: 497m and MWL: 500m are 12,987 MCM and 13,412.6 MCM, respectively, along with live storage of about 9,200 MCM, which are very large to absorb the GLOF volume.

“There are 52 glacial lakes that lie at an elevation between 4,748 and 5,561 m asl in the Subansiri basin are very small and the cumulative area is only 3.088 sq kms. They consist of 27 moraine dammed lakes, 7 erosion lakes, 7 ice-dammed lakes, and 11 other lakes. Moraine-dammed lakes are generally bigger than other types of lakes, and all together they cover 75.25% of the total glacial lake area. Considering their small sizes and changes in size over the study period, most of the glacial lakes do not possess any serious threat of GLOF in the near future.” (Choudhury, S, et al, 2022, Geological Journal, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1002/gj.4403).

The reciprocal dynamics

Himalayan hydropower projects rely on glacier-fed water to generate consistent and sustainable green energy. However, global warming is causing these glaciers to shrink rapidly, increasing the risk of GLOFs that threaten the safety of hydropower dams. Fossil fuel-based thermal power plants, which are primarily responsible for carbon emissions, remain the leading cause of global warming. In contrast, hydropower plants produce clean energy and play a significant role in mitigating climate change, thereby contributing to the preservation of glaciers. (The contributor is consultant, hydropower projects.)