[ Yomli Mayi ]

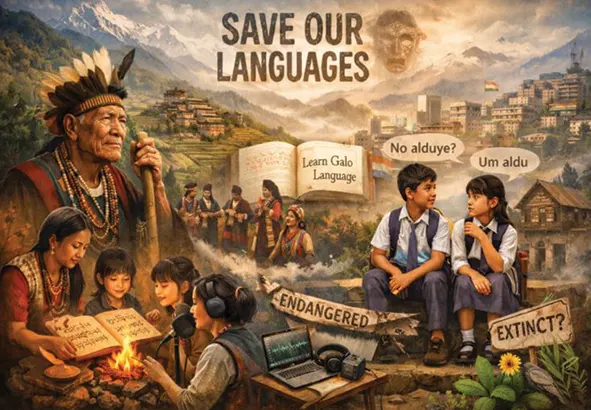

Picture yourself on a hill in Arunachal Pradesh, looking at the eastern Himalayas. This state has a lot of different languages. There are 26 major tribes and more than 100 sub-tribes, with about 73 spoken languages and many dialects. It’s not just about the count – it’s things like Nyishi songs in bamboo areas, Galo stories by the fire, or Mishmi tales in the wind. Arunachal shows how language is important for people. But with more people moving to cities and using Hindi more, these languages might disappear.

Looking at the UNESCO’s 2025 State of the Education Report for India, ‘Bhasha matters: Mother tongue and multilingual education’, during the International Decade of Indigenous Languages (2022-2032), it’s obvious that Arunachal’s languages are key to its people. On International Mother Language Day (21 February), with the theme ‘Youth voices on multilingual education’, young people in Arunachal are getting involved, but we have to ask: Will these languages survive?

To understand languages in Arunachal, we need to know the difference between language and mother tongue. They are similar but not the same. Language is a way people communicate, using sounds, writing, or signs. It’s like the system that helps us share ideas, from simple things to feelings. It has rules like grammar.

In Arunachal, Hindi is the common language that helps tribes like Monpa, Adi, Nyishi, or Apatani talk to each other across different areas.

A mother tongue is the language you learn first as a child. It’s what connects you to your family and background. It holds special knowledge, like names of plants for medicine or old songs that can’t be said the same in Hindi or English. In Arunachal, Hindi helps everyone get along, but mother tongues like Nyishi, Galo, or Mishmi are what make people feel who they are. This is important because Hindi brings people together, but without mother tongues, kids miss out on their own history.

The UNESCO’s report says that mother tongues help kids think better and feel safe, which fits with the National Education Policy (NEP)-2020 that says start learning in a known language. However, the state of mother tongues is in peril. Arunachal has many languages, but they are in trouble. This problem is happening in schools, homes, and towns without much notice.

The UNESCO says that 34 languages in the state are endangered at different levels. For example, Tangam in Upper Siang has less than 50-100 speakers left. Others like Nah, Mra, Bugun, Koro Aka, Milang, Meyor, and Puroik are very close to dying out because not enough people pass them on. In groups like the Aka (Hrusso), only about 7-8% of young people can speak it well. There’s a big difference between generations – kids in places like Itanagar know their language but use only Hindi or English.

This is happening for a few reasons. People move to cities for work, and there Hindi, called ‘Arunachali Hindi’, is used everywhere. Chief Minister Pema Khandu said it’s a choice, but it hurts local languages.

Technology makes it worse because most tribal languages are spoken, not written, so no keyboards or apps for them. Young people who use tech don’t see their languages there. Schools didn’t teach mother tongues for a long time, and experts say kids lose about 10 words a week if they don’t use them at home or school.

Some young people think local languages are old-fashioned and won’t help in jobs. Studies from the government and the UNESCO’s 2025 report list these as the main problems. In the end, languages are used less, and with them, history, nature knowledge, and who people are get lost.

Losing mother tongues in Arunachal is not just about culture – it’s a big problem for everyone. If a language goes away, a tribe’s stories from long ago turn into nothing. People lose their sense of self: Language shows where you come from, and without it, especially for tribal groups, it causes confusion. Old knowledge disappears too – like words for plants in the Himalayas or weather that science is still learning about. In Arunachal, nature and tribal life are connected, so this means losing ways to heal sickness or live without harming the land.

On the thinking side, it’s serious: The UNESCO’s report shows that knowing many languages makes your brain stronger, and learning in mother tongue helps with problem-solving and understanding. Feelings are deeper in your first language – some words just feel right there. Fairness is affected: Without good education that includes languages, tribal kids have harder times keeping things unequal. The report connects this to SDG 4 for fair education. For our state, it’s about keeping a whole way of seeing the world. Other states show what can work: Odisha started its MTB-MLE programme in 2007-08 with the Right to Education Act. It covers 21 tribal languages in 17 districts, with 1,317 schools for nearly 90,000 kids. They have over 3,000 teachers, books made for them, and centres to connect homes and schools for better learning.

Telangana made 274 books in eight languages for Grades 1-10, with mixed language books, digital tools on Diksha, a dictionary in nine languages, teacher training, an app for checking, class activities like language clubs, storybooks in tribal languages like Lambadi, Gondi, and Kolami, and camps for over 121,000 kids.

Arunachal needs to learn from these to stop the loss.

State government’s initiatives

There are some efforts that give hope, but there are still problems. The government’s ‘Third language’ policy is important: They approved 23 indigenous languages, including Galo, Adi, Bhoti, Nyishi, Apatani, Tai Khamti, etc, to teach in schools as a third language. This matches NEP-2020, which says use mother tongues up to Grade 5 for better thinking and feeling safe. Books are made with help from groups like the Tai Khamti Heritage & Literary Society for primers, or ‘Gallo Ennam’ for Galo, from early to higher classes. But it’s not in many places – only 0.3% of schools have three languages, from 2025 data, showing it’s not reaching far (sansad.in).

The department of indigenous affairs (DIA) is key, with Rs 60 crore in the 2025 26 budget for saving and recording things. They do digital saving of old stories, like Nyishi myths and songs, with videos and sounds.

Projects from the NEC check on language work, and the RIWATCH has programmes for mother languages in girls’ schools.

Awards help too, like the National Folk Literature Award-2025 to Gumpi Nguso Lombi for keeping stories, and events like ‘Jazinja: Angba-Binbga’ in 2026 bring young and old together. These connect to the UNESCO’s ideas, like making policies for MTB-MLE with NEP, getting more teachers who know languages, and using digital tools. But without stronger rules, it’s like fixing small holes in something that’s breaking – we need bigger changes.

Not just the government – normal people are working hard too. Groups like the Adi Agom Kebang (AAK) are leading. It’s the main group for Adi language, and they have meetings – the 13th in 2026 was about saving and growing the language. They work on writing and books to keep Adi strong.

Others help too: the RIWATCH Centre for Mother Languages does classes on Kaman Mishmi and records culture. The Nyishi Language Development Board has camps where old people teach kids. Tani Language Foundation, started by young people, uses apps and contests to spread it. Mising Agom Kebang works hard for Mising languages. New ideas include YouTube for songs, music that mixes old and new, and apps for bedtime stories in mother tongues. These show that people are strong and not just waiting – they’re making changes. The UNESCO says make community part of it, and these people show that’s possible, but they need more help with tech and money.

A call to action

For Arunachal, we need real steps, not just words. Begin with ‘speak at home’ plans: Families using mother tongues every day, with events in communities. Make standard ways to write and tech like keyboards, fonts, and AI to help languages online. Schools should change: Teach how to use many languages in teacher classes, hire local teachers, and put third language in more schools, like Odisha’s 3,000 teachers or Telangana’s dictionaries and apps. More events like mother tongue speaking and speech competition at various levels should be encouraged. Proficiency in mother tongue should be preferred in recruitment, especially in the DIA.

The UNESCO’s 10 recommendations are a good plan: Make clear policies for MTB-MLE with NEP 2020; get more multilingual teachers; make community part of it; make books that fit culture with ideas for girls too; use digital things for everyone; push tech that’s fair; make sure money keeps coming; and start a big national group to work together.

For Arunachal, that means the DIA working with groups like the AAK for bigger results.

Being modern doesn’t mean losing old ways – it can help them. Young people, like on International Mother Language Day, are important: Give them apps, events, and school plans that value who they are. If we do something now, Arunachal’s languages will stay. The state needs us – will we help? (The contributor is an independent observer)